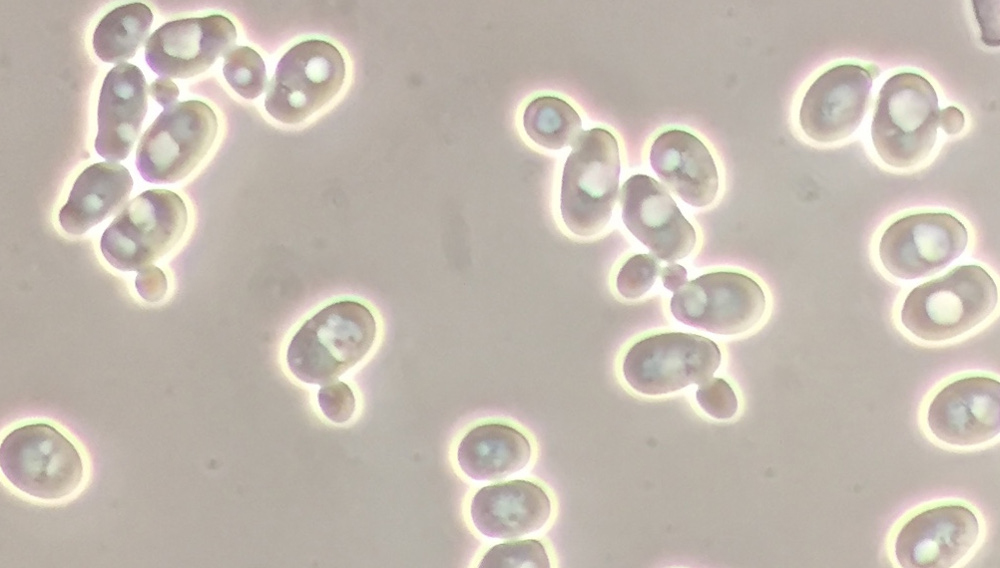

Viability and vitality | Yeast physiology plays a crucial role in producing good-quality beer. Premium-quality beer can only be brewed when the yeast is highly vital and the proportion of dead yeast cells in the pitching yeast is low. Apart from economic factors such as fermentation and maturation duration or technological-qualitative aspects such as clarification and flocculation behaviour during beer production, yeast influences beer qualities such as sensory attributes, as well as foam and haze stability, among other factors.

Process Optimization | The non-alcoholic beverage segment is growing rapidly and will probably continue to do so in the foreseeable future. Therefore, breweries would be well-advised to expand their product palette to offer their customers these beverages. In the production of non-alcoholic beer in-house, whether in accordance with the Reinheitsgebot or not, achieving a high level of microbiological stability while also making a highly drinkable and flavorful product is not easy. The following technical considerations should provide a basis for overcoming these challenges.

Decoding barrel ageing | Wood-ageing shapes the flavour and colour of alcoholic drinks like whisky, wine, and sour beers. Fermented beers aged in barrels for months to a year develop complex flavors, influenced by both wood compounds and (wild) microorganisms [1–3]. To improve consistency, a lab-scale system was developed to study microbial communities and beer chemistry during ageing. This study summarizes findings previously published BrewingScience in 2023 [4].

Quantity and timing | There are many different categories of beer on today’s global beer market, and consumers have certain expectations when they choose a particular type. Most dry-hopped beers are top-fermented e.g. (New England) India Pale Ales, and a certain turbidity is an essential part of these beers’ character. To investigate how haze is affected by dry hopping, a study was conducted to evaluate the influence of pellet quantity and the time of dosage in the cold side of the brewing process.

Raising long-term stability | Part 1 of this two-part series of articles (BRAUWELT International no. 2 2025, pp. 82–86) compared stability of top-fermented, hop accentuated beers and a Pilsener beer. Part 1 also underlined the vital role of esters influenced by hops. Product development, selection of raw materials or production techniques (selection of hop variety, variety mixes, hopping technology etc.) can be a first step towards product stability. This second part of the contribution provides an outlook on which type of stabilisation can be used to reduce any negative changes prior to consumption as far as possible.

What’s that?! There’s a new series in BRAUWELT International? Yes, that’s right. And one that’s not like any of the others? Correct!

Aroma stability | Based on the enormous success of US craft breweries, top-fermented, hoppy beers such as Pale Ales and India Pale Ales enjoyed significant production and sales growth, also in Germany. These beers are characterised by their specific sensory attributes created by dry hopping. As of about 2010, scientific studies initially focussed on reproducibility of dry hopping and achieving a consistent beer aroma with this process. As of about 2015, issues relating to stability of aroma and taste of these beers came to the fore.

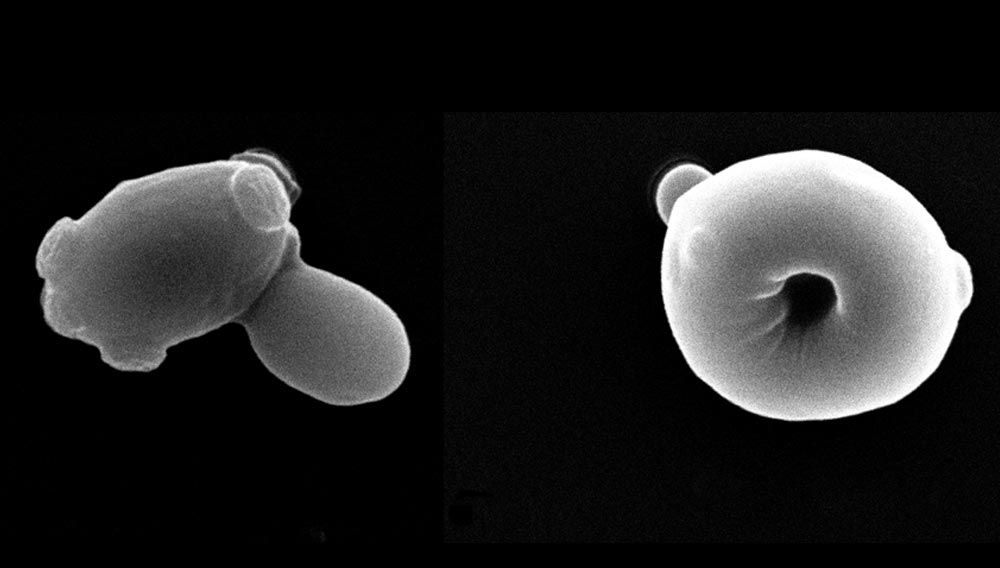

Microbial imperialism | The hybrid yeast S. pastorianus likely evolved spontaneously in the late Renaissance in the beer vats of Bavaria. Since then, it has replaced the once omnipresent S. cerevisiae in breweries throughout the world. This article traces this surprising development from its origins to the present and presents some tantalizing insights unearthed by the most recent genetic research.

The numbers speak for themselves | On the last International Beer Day on 2 August 2024, the German Federal Statistical Office published figures on the consumption on non-alcoholic beer in Germany. Over the last ten years, the amount of alcohol-free beer destined for sale has more than doubled (104 %). The increase in mixed beer beverages is much lower at 11 percent, with the production of beer with alcohol falling by about 14 percent in the same period [1].

Ensuring consistent quality | Kombucha’s popularity is booming due to its potential health benefits. While the production process is straightforward, consistently achieving the same flavor and quality remains a challenge. How can producers ensure consistent quality on an industrial scale?

Mixed fermentation | In recent years, innovations and process optimisations have been observed on a continuous basis in the ever-expanding market for low-alcohol and alcohol-free (< 0.5 %v/v alcohol) beers. In particular various technological processes or combinations thereof (thermal, membrane or biological processes) led to a strong diversification of the market.