Getting to grips with brewers‘ yeast | Yeast – driving force, flavourist, complex entity and challenger. There is more to this small organism than meets the eye. Controlling brewers’ yeast is primarily essential for beer quality as it has been subjected to some technological transformations in the course of time.

Biosynthesis | It was found recently that brewers’ yeasts not only break down and convert hop aroma substances such as linalool and geraniol during fermentation, they can also form them. Though these processes take place in the microgram range, they nevertheless change beer flavour. This may be influenced by selection of a brewers’ yeast strain [1].

Beer analyses | The Omnium brewhouse concept by Ziemann has been operating successfully for the first time in a German brewery, Schlossbrauerei Reckendorf, since the beginning of April 2018 [1]. In the first part of the technological considerations, the results of brewhouse operation based on process times and data from wort analyses were explained [2]. The repercussions for beer quality resulting from technological factors described will be examined in this second part of the article.

Less is more | When producing beers using ale yeast strains in the pilot plant of the University of Weihenstephan-Triesdorf, fluctuations occurred in sensory quality of 50-l pilot brews. In some instances, beers were described as “lacking body” and as “empty”. It was assumed that this was due to excessive addition of dry yeast. As a consequence, a pilot fermentation process on a 0.5 litre scale was developed in order to obtain information about fermentation rapidly and with little expenditure.

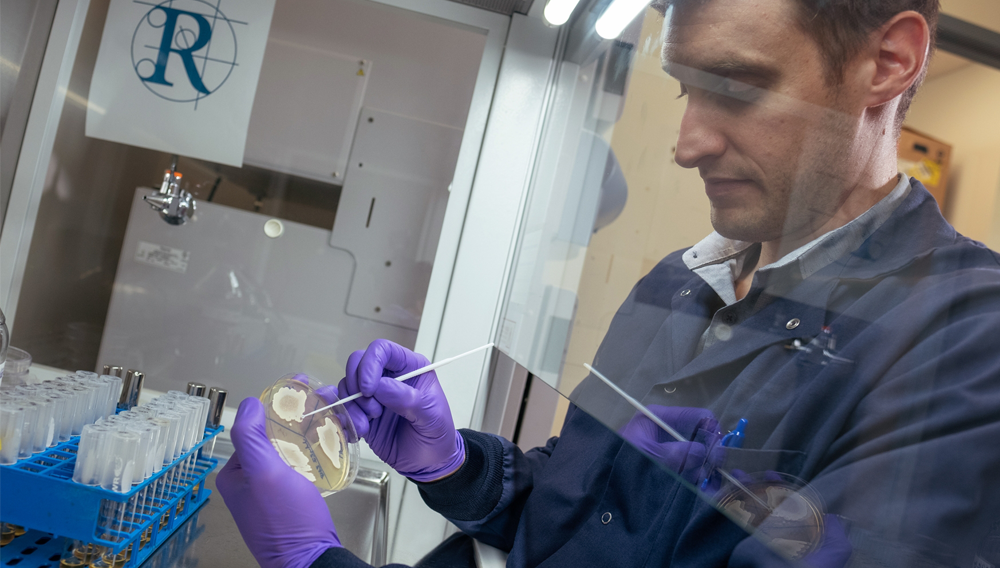

Searching for innovations | Beer, the traditional beverage, is losing many consumers in the face of many new and innovative beverages. Innovations in the beer sector such as novel hop varieties or targeted use of different malts, as well as a great variety of different shandies, have already reversed this trend to some extent [1]. Continuing along the same lines, a method aimed at producing new brewers’ yeasts is presented.

Flavour and aroma variety | Yeast’s impressive natural biodiversity has often been overlooked in modern industrialized brewing in favour of workhorse yeast strains that offer consistency. Today, in an age of rapid expansion in brewing creativity, yeast’s biodiversity is being harnessed to help fuel innovation in beer making.

First International Workshop on Brewing Yeast | Yeast scientists and brewing technologists from all over the world met on 5 - 6 October 2018 in San Andrés de Bariloche, Argentina, to share their latest research findings on brewing yeast.

Designing Yeast | In this concluding section of our three-part series (part 1 and 2 see BRAUWELT International No. 5, 2018, pp. 354-356 and No. 6, 2018, pp. 430-432) we outline the various non-GMO methods by which new brewer’s yeast are being created to drive beer flavour and aroma innovations. By applying the classical technique of selective breeding – used for millennia in the domestication of species – it becomes possible to re-imagine brewer’s yeast, thereby enhancing and expanding yeast’s natural ability to define beer styles and flavours.

Controlling yeast | In the first part of this three-part article (BRAUWELT International No. 5, 2018, pp. 354-356), we outlined the enormous impact yeast has on the flavour and aroma profile of beer. In this sec ond part, we discuss the variables and methods by which brewers can exert direct control over yeast during the brewing process. In the concluding article, we will examine the time-honoured, non-GMO classical development techniques by which new and exciting yeasts are being developed to help create whole new flavour and aroma profiles in beer.

Describing flavour | Continuing our series on the topic Better Yeast, Better Beer, here we provide the first part of a three-part article explaining yeast’s significant potential in developing revolutionary new beer tastes and flavours to meet rising consumer demands for innovative beer tastes. In part two, we examine the many variables that brewers can exploit to modulate yeast impact on beer flavour and aroma. And finally, in part three, we explore the idea of developing novel brewer’s yeast strains, using classical non-GMO techniques, to help deliver better yeasts for better beer.

Yeast recycling | Yeasts are usually used for one fermentation cycle in industrial fermentation. In the brewing industry, however, yeasts are recycled several times, also as a result of a continuous succession of production processes. Consistent and, in particular, reproducible fermentation results have to be obtained. Optimal yeast management is required in order to achieve this objective. Moreover, the number of cycles is crucial for fermentation performance and depends on the yeast strain as well as on the experience and philosophy of the brewmaster.