Beer/Brewing history

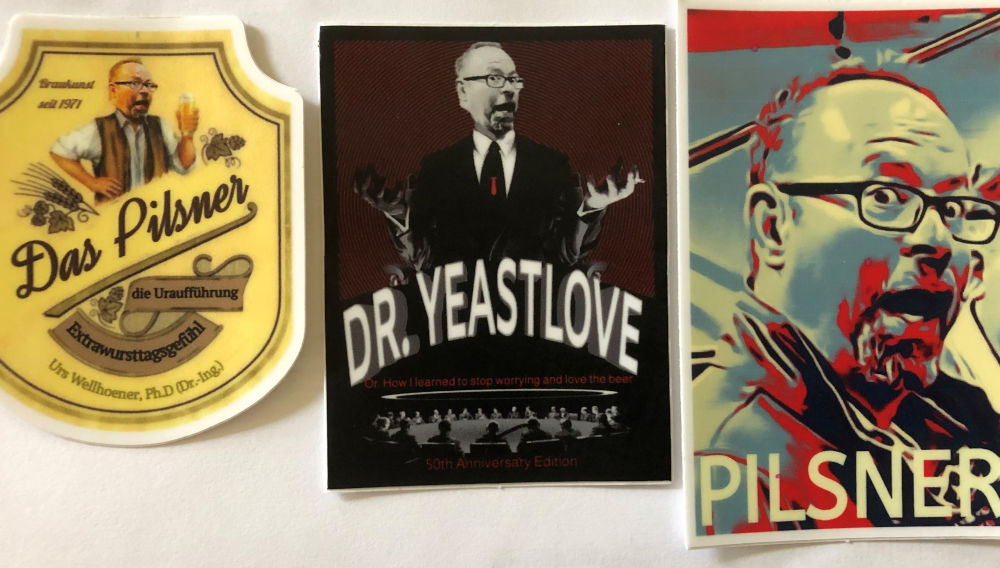

Family history | It certainly happens from time to time that a brewer serves self-brewed beer for a special birthday. The fact that this beer was fermented with the brewer's yeast discovered by his grandfather is the absolute exception. Dr. Urs Wellhoener, Technical Director Brewing Innovation at The Boston Beer Company, Boston, MA, USA, was lucky enough to treat himself with this special brew for his 50th birthday, and BRAUWELT talked with him about his “birthday beer”.

Beer/Brewing history

Seven classics | The concept of the Trappists and their beers was explored in the first part of this series. The author also introduced the new generation of Trappist breweries, namely the five where brewing commenced between 2012 and 2018 (BRAUWELT International no. 6, 2020, pp. 440–442). In this second installment in the series, the focus will be on the traditional Trappist breweries.

Beer/Brewing history

Ora et labora | Anyone who has anything to do with beer is certainly familiar with the term “Trappist ale”, and most have likely already tasted at least one of them as well. But what is the story behind Trappist beer?

Beer/Brewing history

Summer school | Although still in its pilot phase, 2018 marked the first collaboration between the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (VT) and the Technische Universität München (TUM) in the form of an exchange program for brewing and food technology students.

Beer/Brewing history

Beers of the world | Lambic is the revered yet mysterious beer native to the Pajottenland, a region to the southwest of Brussels between the rivers Dender and Zenne in Belgium.

Beer/Brewing history

Beers of the world | Helles and its associated styles Dortmunder Export, Festbier, Leichtbier and Kellerbier/Zwickel are fairly recent developments in the world of beer that started becoming popular only about one hundred years ago. All these beers have a yellow to gold color, high sessionability and a malty profile in common. They are generally well-rounded and evenly balanced.

Beer/Brewing history

Flemish Red Ale is the name for beers produced in the north western province of Belgium, West-Flanders. The province hugs all the coast of Belgium and everyone seems to know Bruges, the capital of the province.

Beer/Brewing history

Wort and Must | Due to its location on the Continent and its dynamic history, tiny Belgium looms large in the beer world. Its past is awash in successive waves of Celto-Germanic beer and Roman, French and Spanish wine. It is one of those regions of Europe where the grape and grain have intermingled over time but in an inimitable manner as could have only transpired in a country on the edge of the Roman Empire and the North European Plain, nestled between the English Channel and France, the Netherlands, Germany and Luxembourg.

Beer/Brewing history

Over the last twenty years IPAws have become the most popular craft beer style in North America. This trend has spread to other beer markets around the world, and in some areas “India Pale Ale” is synonymous with “craft beer”. As part of the spirit of experimentation of craft beer and to differentiate their products from others, brewers introduced new variations of IPA, and with that many IPA sub-styles have evolved. The most popular of these will be the focus of this article: Belgian IPA, Black IPA, Brown IPA, New England Style IPA, Red IPA, Rye IPA and White IPA.

Beer/Brewing history

Schwarzbier is one of the oldest beers of Central Europe. Like Munich dunkles and Düsseldorf altbier, it is a relic of the once virtually unbroken landscape of dark beer that spread across Europe north of the Alps.

Beer/Brewing history

Hopalong on the lupulin trail | In the wake of the gradual, millennium-long adoption of hops as the primary brewing herb in Europe and thus the world, modern brewers are often not aware that other herbs were used in beer production. In the article “Of Cones and Cauldrons, Hops and Gruit” (BRAUWELT International No. 1, 2019, pp. 20-23), alternative brewing herbs and their use by modern craft brewers were touched upon. In this issue, hops and a mostly long-forgotten practice associated with their usage will be discussed.