Schwarzbier

Schwarzbier is one of the oldest beers of Central Europe. Like Munich dunkles and Düsseldorf altbier, it is a relic of the once virtually unbroken landscape of dark beer that spread across Europe north of the Alps.

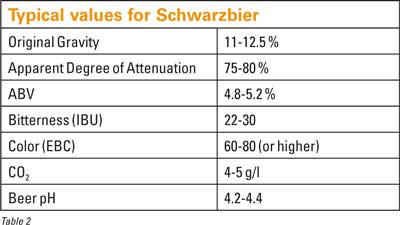

Malty, roasty and very dark, schwarzbier has not always been bottom-fermented but all modern representations of the style are. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, it was hailed as a wholesome, nutritious beverage. Though it had been brewed in the region where it originated for a number of centuries, the spread of more advanced malting technology, pale lager brewing and the devastation and neglect of the 20th century almost brought about the extinction of the beer. Remarkably, schwarzbier survived, and since German reunification, this unique style has experienced a surge in popularity in its home country and around the world.

Origin

Schwarzbier as we know it today originated in the regions of Saxony and Thuringia. These two German states are situated on the great North European Plain, where beer has been brewed for thousands of years. Barley, wheat, oats and rye were cultivated by the tribes on the northern periphery of the Roman Empire for beer production. Thuringia and Saxony do not belong to the lands of Germany that at one time were located behind the Roman “Limes” (the Empire’s northern border), where the inhabitants learned viniculture and continue to practice it today, that is, unless the chilly climate of the Late Middle Ages put a stop to it. On the contrary, the peoples of Saxony and Thuringia were well north and east of direct Roman influence, and the climate, even during the relatively warm spell of the High Middle Ages, would not have permitted much wine production. A few hillsides along the rivers Unstrut, Saale and Elbe have, in fact, been found capable of yielding grapes worthy of a vintner’s time and attention (the number of vineyards is increasing with the changing climate). Thus, organized viniculture was never practiced there on a large scale as elsewhere in German-speaking regions of Europe. Beer was and continues to be the “Volkstrunk” (the beverage of the common man) of Saxony and Thuringia. Records show that Leipzig had over 200 breweries in the Late Middle Ages. These areas did not fall under the Bavarian purity law of 1516; however, as unscrupulous brewers all over Europe occasionally adulterated beer with questionable, unpalatable and perhaps even dangerous ingredients, the cities of Weimar and Weißensee in Thuringia also issued laws stating that only malt, hops and water were permitted in beer. Theirs even predated the Bavarian decree. Weimar’s statute was found in the city’s archives in a text called the “Bürgerbuch” dating to 1348 and was written in a Central German dialect. Since the type of malt is not specified, malted barley, oats and/or rye would most likely not have been out of place in medieval schwarzbier, especially since the latter two cereal grains are well-adapted to the harsher climate conditions north of the Danube and east of the Elbe, and they are also not as suitable for making bread as other grains. Though schwarzbier is now only bottom-fermented, this was surely not always the case. Nevertheless, under the contemporary purity-law-inspired “Vorläufiges Biergesetz” of Germany, bottom-fermented beers must be brewed with 100 % malted barley in the grist.

Medieval beers made from kilned malts were often referred to as “schwarz” (black), “braun” (brown) or “rot” (red), while beers brewed with wind (air-dried) malts were “weiss” (white), independent of whether they contained wheat or not. Schwarzbier is first mentioned in the 14th century. One famous schwarzbier can be found in the town of Bad Köstritz in the state of Thuringia, southwest of Leipzig, Germany. “Kostricz”, as its founders called it, was established in the Middle Ages by Slavs, and brewing has a very long history there. Slavs brought the practice of cultivating hops and brewing hopped beer west to Central Europe. The Köstritzer Brewery was founded in 1543 and is therefore one of Germany’s oldest. Beer has been served for at least 500 years in two of the town’s venerable public houses, which for centuries were passed down through kinship (“Erbschänken”). The “Obere Schänke” and “Untere Schänke” (“upper” and “lower”) are now called “Zum Goldenen Kranich” and the “Goldener Löwe”, respectively. Students from the nearby University of Jena, which was founded in the 1500s, helped ensure that production of schwarzbier did not flag in the region. Just over the Erzgebirge from the famous Western Bohemian spa town of Karlovy Vary, Köstritz has been a site sought out by those desirous of treatment in healing baths, chiefly since the mid-19th century. In fact, in 1926, the town was officially given the name of “Bad Köstritz” (“Bad” in German place names refers to a spa town where “Heilbäder” or healing waters are present). With recognition of Köstritz as a spa town, schwarzbier was also given the status of “Nähr- und Kraftbier”, a kind of nourishing healthful beverage “low in alcohol, recommended by doctors” (fig. 1). The water around Leipzig contains substantial quantities of minerals, and this provides a clue as to not only why the region’s healing waters are so revered but also why dark beer persisted there.

About 100 km north of Bad Köstritz, near Leipzig, there is another medieval town famous for dark beer, called Krostitz (one can be forgiven for confusing the two). The town first found mention as “forwerck Crostewitz”, and schwarzbier has been brewed there for centuries as well. In 1631, during the Thirty Years’ War, King Gustavus Adolphus was a guest at a manor in Krostitz, where according to legend, he was served the local beer brewed for an approaching harvest festival. Upon draining his tankard, he was apparently so impressed with the beer that he presented the brewer with a golden ring inset with a ruby in appreciation.

The water in both Bad Köstritz and Krostitz is quite hard (around 20 °dH). Brewers today can brew any beer style with modern water treatment, pH meters and precise mash acidification. But in past centuries, brewers simply knew that without a certain amount of darker malts in the grist, they would have problems downstream in the brewing process and with the finished beer. Prior to water treatment and the advent of modern production practices, many Central Europeans, including those around Leipzig, drank dark beers.

Pilsner originated next door in Bohemia, and with its meteoric rise in popularity as well as the increase in export shipments, the production of many darker beers slowly fell into decline. As scientific knowledge advanced, malting and brewing technology continued to improve. It became possible to kiln malt indirectly with coke, more consistently at lower temperatures and in a gentler manner. Pale malts and thus pale beers became more widespread.

Under Communism, production methods were compromised, and schwarzbier was sold as a specialty drink for export to other Eastern Bloc countries. It was not allowed into West Germany at the time due to the addition of sugar, intended to enhance the beer’s flavor. In 1989, annual production of schwarzbier amounted to around 12 000 hl in Bad Köstritz. However, deep-rooted brewing traditions were resurrected after reunification in 1990, when authentic schwarzbier began to be brewed once again. Since then, the beer style has undergone a renaissance and a rapid rise in popularity.

Appearance/Aroma/Flavor

Given that its name means “black beer” in German, it should come as no surprise that schwarzbier is very dark – from a deep reddish brown to pitch black – and is topped with cream-colored, finely filigreed foam. German schwarzbier is best described from a sensory standpoint as an elegant, complex yet delicate balancing act between malty and roasted flavors, complemented on the palate by the subtle, refined bitterness of dark malts and noble hops with a refreshing effervescence. If there is any sweetness on the palate, it is very slight. The beer has a light to medium body. Due to the bottom-fermenting yeast, there is a general absence of fruity esters or other ale-like fermentation by-products in the nose and on the palate. Rather, a pleasingly sharp, pure lager crispness is evident, in which the dark malt and the mild hop bitterness come to the fore. Though darker malts provide color and flavor to the beer, there are no acrid or astringent burnt notes, only those reminiscent of bitter chocolate and roasted grain or chestnuts. The finish is pleasant and invites the drinker to further imbibe. A Bohemian version of schwarzbier exists, too. It tends to exhibit a less pronounced hop bitterness and a slight sweetness with a touch less alcohol and a hint of diacetyl.

Schwarzbier is a style offering a lot of potential for creativity. Craft brewers have produced notable interpretations of the style by more profoundly accentuating the various nuances unique to the combination of dark malts and bottom-fermenting yeast, including roasted malt, cocoa, coffee, caramel, licorice and smoky notes as well as silky qualities. The style can be fascinating when dry-hopped, since it provides an outstanding canvas for a more well-defined and focused intermingling of dark malts and volatile hop compounds rarely found in other beer styles with more fragrant and dominant fermentation by-products.

Schwarzbier should be drunk at approximately 8 °C from a relatively bulbous glass. In fact, there is a chalice-shaped glass in Germany known as the “Schwarzbierpokal”, depicted on the right-hand side of figure 2. The beer pairs well with peppered, braised or smoked meat, barbecue, traditional goulash, grilled vegetables and aged, nutty cheeses.

Ingredients

Grains

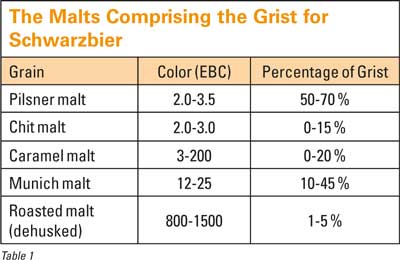

As mentioned, German schwarzbier is brewed with 100 % malted barley. Munich malt contains viable enzymes, although their activity may be somewhat diminished. Caramel malts are available in considerable variety, from light to dark. The combination of malts in the grist should impart a rounded mouthfeel without being burdensome and malty as well as roasted aromas and flavors. The darker Munich and caramel malts should be used sparingly, since honey-like notes or those of dried fruit are completely absent or at least not very pronounced in schwarzbier. The same applies to the black treacle, dark toffee or sherry-like flavors one finds in heavier dark beers. For a finer bitterness, dehusked roasted malt can be employed. Chit malt can also be added to improve starch conversion, foam formation and head retention, if the primary malt in the grist is too highly modified for German-style brewing, and can also serve to provide a more satisfying mouthfeel (see table 1).

Hops

Noble German or Bohemian varieties are recommended for both bittering and aroma. These hops impart a delicate bitterness, which is desirable for this style. A balanced, perceptible but not overpowering hop aroma from a late brewhouse addition would not be out of place for traditional schwarzbier.

Other ingredients

The color of some commercial examples of this style is increased or corrected with a product known in German as “Röstmalzbier”, which is a Reinheitsgebot-sanctioned coloring agent made from fermented barley malt wort. Very little is required as it is extremely dark (8100-8600 EBC, fig. 3), very stable and can be added at almost any point in the process, from casting out of the wort kettle to packaging. It is best to add it where there is some mixing, such as in the wort kettle, when transferring to the maturation tank, immediately prior to filtration, in the bright tank, etc. The dosage rate is ordinarily 14 grams per EBC unit of color per hectoliter of product.

Yeast

German bottom-fermenting yeast of the strain used to brew pilsner or helles is suitable for schwarzbier. A Czech lager yeast would be appropriate for Bohemian

schwarzbier.

Brewing process

Wort production

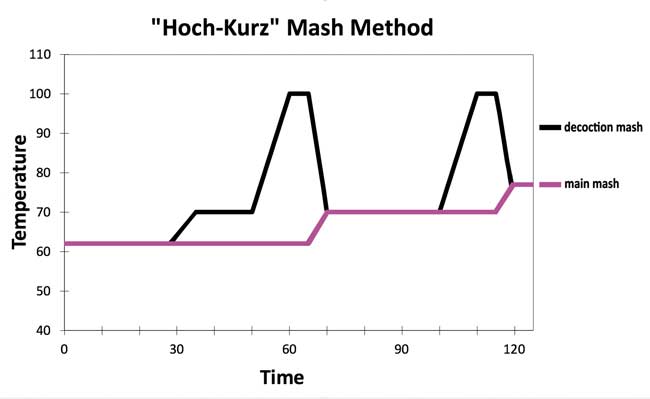

Infusion or decoction mashing is suitable for producing schwarzbier wort. Decoction is especially practical if the gelatinization temperature of the starch in the malt is higher than normal. A “hoch-kurz” mash method (fig. 4) can be employed if the protein content of the malt is ≤ 10.8 % and the Kolbach index is ≥ 40 %, otherwise a more intense mash method with a protein rest would be prudent. Decoction mashes can also be held at 90-95 °C rather than boiled at 100 °C. Given the addition of darker malts, a pH adjustment may not be necessary in the mash or the wort. Some brewers prefer to add the roasted malt in the lauter tun to achieve a finer bitterness.

Depending upon the intensity, schwarzbier wort can be boiled for 1 to 1.5 hours. The bittering hops should be added an hour before the end of the boil. Another addition at the midpoint of boiling will impart a more pleasant bitterness to the beer. If there is a late addition in the brewhouse, it is normally low.

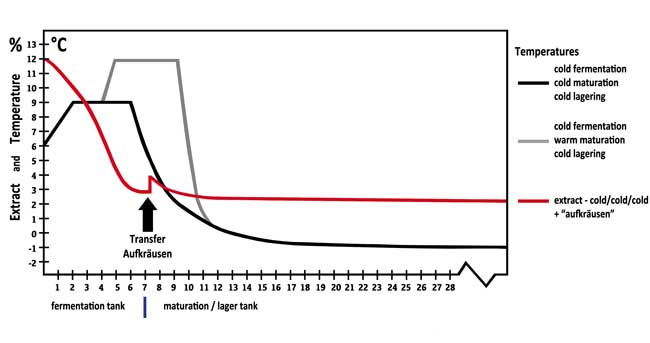

Fermentation

As a bottom-fermented beer, the yeast is pitched at around 6-8 °C (15-20 million cells/ml) and primary fermentation is conducted between 9 °C and 12 °C. A long, slow fermentation and maturation will result in a finer aroma, a better flavor, creamier foam and a generally more drinkable beer (fig. 5, black line). A diacetyl rest (fig. 5, gray line) towards the end of fermentation helps ensure that the diacetyl remains below the sensory threshold in the finished beer (enough valine, i.e. FAN, in the wort will also inhibit diacetyl production during primary fermentation). The drop in extract for cold fermentation (no diacetyl rest), maturation and lagering is also depicted in figure 5 (red line).

Maturation

It is common practice in Germany to use a bung device to “spund” the maturing beer, i.e. the tank is sealed while the beer still contains residual extract, so that natural carbonation can occur. It is also possible to “aufkräusen” (red line, fig. 4), meaning that the green beer is mixed with fermenting wort at high kräusen (at 20-25 % attenuation and equal to approx. 8-12 % of the green beer volume). The residual extract ferments gradually during maturation and lagering with the temperature slowly falling from 4-6 °C down to - 1 to 0 °C over several weeks, where it is then held for a similar duration. Using traditional fermentation and lagering methods produces beer with a more rounded flavor, delicate carbonation and inviting liveliness as well as dense foam; however, tanks must be rated to withstand the required level of overpressure. Gravity readings should be carefully monitored to ensure they are consistent between batches in order to obtain the same level of carbonation each time.n

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kristian Huber and John Hannafan for their spirited and insightful conversation as well as the breweries Köstritzer and Krostitzer for providing the images of their products.

References and further reading

1. Back, W. (Editor): “Ausgewählte Kapitel der Brauereitechnologie”, Fachverlag Hans Carl, 2008.

2. Meußdoerffer, F.; Zarnkow, M.: “Das Bier: Eine Geschichte von Hopfen und Malz”, C.H.Beck Verlag.

3. Narziss, L.: “Abriß der Bierbrauerei”, 6th edition, Enke Verlag, Stuttgart, 1996.

4. Narziss, L.; Back, W.: “Die Bierbrauerei – Band 2: Die Technologie der Würzebereitung”, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA.

5. Sacher, B.; Becker, T., Narziß, L.: “Some reflections on mashing – Part 2“, Brauwelt International No. 6, 2016, pp. 392-397.

Authors

Nancy McGreger, Christopher McGreger

Source

BRAUWELT International 2, 2019, page 117-120