Porter was recorded as a distinct beer style in the 1700s in London, England. The name of Porter is said to have come from its popularity with the porters handling produce in the various wholesale markets located in the city.

This amber lager dominated the beer market in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and beyond. People particularly appreciated its relatively light color and, thanks to a long cold maturation period, its high drinkability, which top-fermented beers couldn’t compete with.

Puckering Pellicles | Words like complex, mysterious, ancient, wild and artisanal are used to evoke the enigmatic nature of lambic. Few, if any, beers instill such awe and reverence in enthusiasts and connoisseurs – one reason that lambic and its production process are safeguarded by the European Union under a quality scheme designed to protect traditional foods.

Despite the image of a medieval and monastic heritage, Belgian Tripel (as we know it today) is quite a modern style. The Tripel family exemplifies the Belgian way of brewing very well: the rich, estery and phenolic aroma profile is paired with a dry body which gives these beers a very high drinkability considering the high alcohol content.

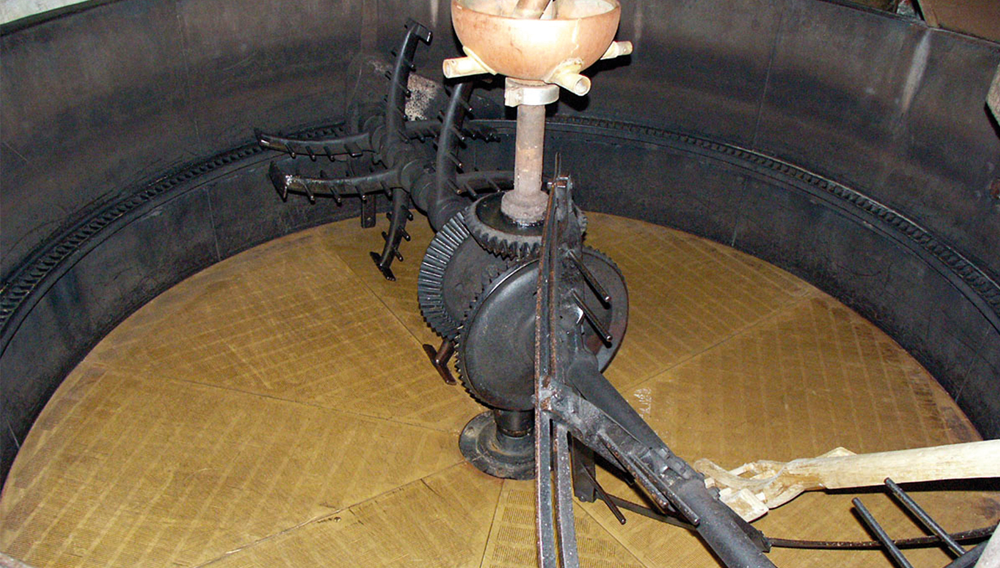

Coppers and Coolships | Since the authors first began visiting lambic breweries in the late 20th century, the popularity of this distinctive Belgian beer style has blossomed. Lambic now serves as an inspiration for creative brewers around the world with a thirst for exploring the enchanting realm of “wild” fermentation, a taste worth acquiring. In this installment, the discussion moves from mashing on to lautering, boiling and cooling the wort.

Degradation and Digestion | Lambic is a fascinating beer style for many reasons, one of which is that unlike most other beers, a wide range of microbes ferment the wort. When one part of beer production is clearly out of the ordinary, then the brewing process tends to be unorthodox in its entirety. This is most certainly the case for lambic.

Love it or hate it, there’s no disputing that corn and rice-based adjunct lager beer has long been America’s national beverage. Indeed, when viewed strictly based on sales, or the number of countries where brands representative of this style of beer are ranked first, one could argue American-style lager beer is planet earth’s preferred beverage when it comes to beer!

Like many of the lesser-known beer styles that originated in Germany, the production of “Märzen” has been in steady decline. Many beer drinkers are familiar with the term but may have never enjoyed a glass of the beer themselves. Despite its close relationships to Bavarian Helles and Munich Dunkel, the style warrants closer exploration. Its malty notes combined with a subtle sweetness create a beer that is very sessionable yet showcases a lot of complexity.

Zenne and the Art of Brewing | The BeNeLux region owes its reputation as Europe’s “cock fighting arena” to its tumultuous history. Belgium itself is even split in two: the Walloons occupy the south and the Flemings the north, with a small German-speaking enclave off to the east. The region’s past fueled the rise of unique brewing traditions throughout this dynamic corner of the Continent.

Weissbier has become the most popular beer style in southern Bavaria after almost dying out in the middle of the last century. Weissbiers are now available in many places across Europe and are also a staple in the line-up of many craft breweries in the US. The name means “white beer”, referring to the color (not the use of wheat) and was used to distinguish the style from the brown beers that were predominant in the middle ages. Today “Weizen” (“wheat”) and “Weisse” (“white”) are used interchangeably and refer to the same beer.

For more than 100 years Mild Ale was the most popular style of beer in the UK, before going into a catastrophic decline in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Still accounting for 50 per cent of sales in 1960, by 1980 that was down to eleven per cent and by 2000 it was below two per cent.