The lapse of luxury

Forget the razzmatazz of this season’s couture shows. Away from the catwalks, the couture industry has lost its swagger amid a global slump in demand for luxury goods. Several fashion labels have been forced to lay off staff, including Burberry and Chanel, it was reported. French luxury goods giant LVMH reported a slump in demand for watches and jewellery. So much for the myth that luxury goods are recession-proof.

Luxury good sales are forecast to fall 15 percent this year, according to Bernstein research, reflecting the unprecedented global wealth destruction. Middle East sales are static. Russia is wobbling. Asian interest is not very high.

The impact of the economic crisis is being felt across all segments as consumers trade down or cut unnecessary expenditure.

This forces branded goods groups to reflect upon the issue of how much of the slump is cyclical and how much it reflects a permanent shift in consumer behaviour.

There is no doubt, however, that the good times are over. Between 2003 and 2007, the global luxury goods market grew on average 7 percent per year to USD 170 billion, fuelled by soaring asset prices. A new word even had to be coined – plutonomy - to describe a world in which an ever-expanding minority of ultra-wealthy individuals responsible for a disproportionate share of disposable income would fuel permanent rapid growth in demand for luxury.

Much of this growth was expected to come from emerging markets, where demand was projected to grow by 35 percent over the next five years.

The sudden turnaround is a strategic dilemma not only for luxury goods groups, such as the purveyors of USD 2,000 handbags, but also for mainstream consumer goods companies that betted heavily on "premiumisation" - the attempt to move brands upscale to attract more affluent, status-conscious consumers.

Will conspicuous consumption – the flashing of high-end labels – continue to be the done thing in public or will there be a permanent backlash against ostentatious wealth?

Branded goods companies must decide whether to defend their premium prices and risk losing market share or whether to try to reposition the brand. The risk is that cutting prices could permanently destroy brand value.

This new environment is sure to claim many casualties among brands.

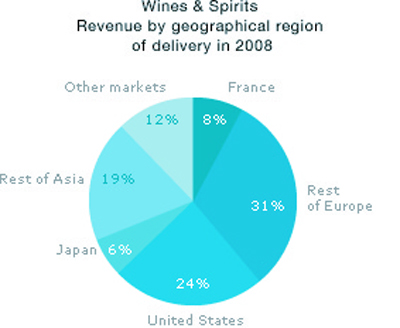

The winners will be the mega-brands that can outspend rivals on advertising and promotion as a proportion of sales. Also well placed are luxury goods groups with well-diversified portfolios, both across product categories and geography.

LVMH, the French luxury goods group, said that it was able to offset the weakness in watches and jewellery with strong performances from fashion and perfume brands.

Similarly, drinks giants Diageo and Pernod Ricard should also do well since they can offset some of the losses on premium brands with gains on their long tail of cheaper, mainstream brands.

Global scale is crucial since in the long-term much of the growth is still likely to come from emerging markets.

But the biggest winners of all will be those who can reposition their brands to capture the mood of the times. And convince their customers that “thrift was no virtue during a recession” (John Maynard Keynes).

Source

BRAUWELT International 2009