Beer market woes take their toll

Dr Isaac Sheps, CEO of Baltika Breweries, who resigned on 27 November 2014, is the most high-profile casualty of the Russian beer crisis to date. Only three years ago he had been posted to Russia from Carlsberg UK and replaced Baltika’s then head Anton Artemiev, who had failed to prevent a slump in Baltika’s profits amid declining beer volumes and steep tax hikes.

The situation in Russia has not got any better since. In fact, the beer market continued to decline every year, taking total volume losses to over 20 percent between 2009 and 2013. Things got somewhat worse this year as the Russian economy has been struggling with a weakening of domestic demand and high levels of inflation, amid geopolitical issues with the Ukraine.

Worse still, the ruble currency has slumped by close to 40 percent against the dollar since the start of the year, and over 30 percent to the euro. As Carlsberg reports in Danish krone, which is pegged to the euro, you can work out for yourself what this could mean for Carlsberg’s 2014 profits from Russia.

Carlsberg said in November that it is sticking to its latest forecasts for a decline in profit of under 10 percent for the full year. Let’s hope Carlsberg did its currency hedging transactions in time.

Carlsberg is not the only international brewer struggling in Russia. All are burdened with production overcapacities. Carlsberg, AB-InBev and Efes have reported brewery closures this past year and, as early as 2009, Heineken started closing breweries. That’s why it will make interesting reading how much the three international brewers will write down the value of their Russian assets in their 2014 annual reports.

But the practical question remains: what to do with a brewery in Russia that is surplus to your requirements?

Heineken was the first foreign brewer to close two breweries. In 2009 it turned the Stepan Razin brewery in St Petersburg into a logistics centre and shut down the Ivan Taranov facility in Novotroitsk close to the Kazak border. These brewery closures came before the recent beer market malaise and were aimed at improving overall efficiency and profitability.

AB-InBev came next. Over the past two years its subsidiary SUN InBev has shuttered four plants: Novocheboksarsk, Kursk , Perm and most recently Angarsk in East Siberia. AB-InBev would not say what has become of the plants made redundant, but rumour has it that at least the Siberian brewery’s kit will be re-used once shipped to near-by China.

Already at the end of 2013, Efes Rus, the Russian subsidiary of Turkish brewer Anadolu Efes, announced the closure in Russia of two breweries in Rostov-on-Don and Moscow. Observers say that Efes is currently clearing its Moscow site because it is confident it will find a buyer for the remainder of its lease on the land.

Carlsberg’s Baltika with ten breweries across Russia has longest resisted any brewery closures. Only in September 2014 did Baltika stop beer production at its Chelyabinsk and Krasnoyarsk plants. A spokesperson said the two breweries are to be mothballed and “production is expected to resume as required by market demand”. That may turn out to be a pious hope because from what we hear Baltika’s flagship brewery in St Petersburg is only working at 40 to 50 percent capacity and more breweries could be shut down.

People familiar with the situation say that, while tanks as well as bottling and packaging equipment from all these disused breweries could find new homes, several brewhouses might end up as scrap metal because there is no second hand market in Russia for such large plant items.

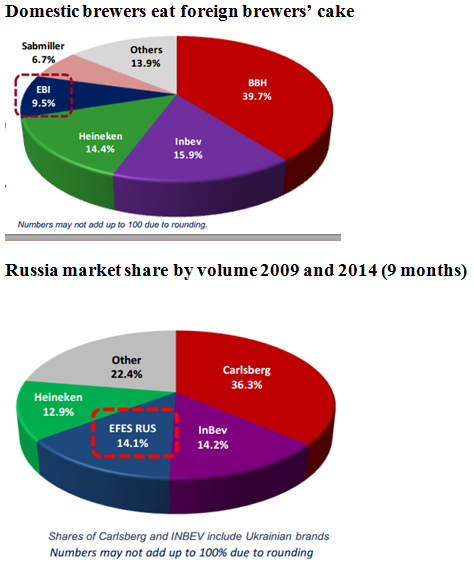

It may have escaped our notice that over the past four years, the number of breweries in Russia has doubled: from 250 to 540 according to estimates. Obviously, this figure also includes brewpubs. Nevertheless, domestic brewers’ total market share has risen from 14 percent in 2009 to 24 percent in 2014, or from 15 million hl beer to 21 million hl.

Many of the larger domestic operators would like to buy the disused brewhouses, if they were not too big for their requirements (which are around 400,000 hl of annual capacity). Behind these breweries are often distributors and clever businessmen who see opportunities in the market for their high-quality and premium-priced beers.

What does this mean for the regularly re-hashed argument that over-regulation and rising taxes on beer are to be blamed for international brewers’ Russian plight? Well, it seems that the true picture is much more complex than international brewers would like to admit.

While there are some grounds for the sneaking suspicion that Russia’s powers-that-be have taken a dislike to foreign ownership of the Russian brewing industry – in recent years consumption of beer has shifted back to vodka again, which should please the 100 percent Russian-owned vodka industry – there is equally no denying that international brewers only have themselves to reproach if some of their volume went to their domestic rivals. It would not be fair to assume that domestic brewers fare better under the current regime: they too suffer from the general anti-beer mood.

Although some market observers seem to believe that Russian beer consumption will not drop any further, I’d say that the jury is still out. Russia is heading towards a recession in 2015 and, in view of high inflation and rising costs of living, Russian beer drinkers cannot be faulted if they turn to drinking more samogon (Russian moonshine) instead.