Are manganese levels in wines a real worry?

Following the catastrophic melamine-contamination scandal of 2008, the Chinese authorities and Chinese consumers have become understandably nervous about other possible contaminants in food and drink products. But why manganese in imported wines has now been singled out by the Chinese authorities as a “baddy” leaves a lot of room for wild speculation.

A statement by Wine Australia – a Federal agency – of March 2014 advises Australian vintners that the Chinese authorities have imposed a limit (2mg/L Mn) for the naturally-occurring trace element manganese, a limit which may be exceeded in wines from many countries, including Australia.

In the past 12 months there have been reports of 14 Australian wines having been challenged after being analysed for manganese on arrival in China. No one knows how much wine in total was rejected, although Wine Australia believes that the volumes were low. The federal agency is not aware of any country other than China that imposes such a limit on manganese content.

All this has Australian vintners seriously worried. After all, it will be remembered that in the past China’s neighbour Russia has used bans on imported wines and other food stuffs because of spurious health concerns as a tried and tested form of political pressure. In the recent past Georgian and Moldovan wines, Lithuanian dairy products and Tajik nuts have all fallen foul of sudden injunctions.

The reason manganese is so prevalent in Australian soils, says the Australian geologist and consultant Paul Harvey, is that geologically Australia is a very ancient and stable continent. “As a result many Australian soils are very old and have developed through chemical rather than physical erosion processes. As manganese is a fairly refractory element it tends to be concentrated in these soils and I suspect manganese levels in many Australian soils are higher than many other areas around the world.”

The Chinese authorities may think otherwise, but in the rest of the world manganese is considered an essential nutrient. So‐called “superfoods” like chia seeds are rich in manganese and many people take manganese supplements.

Nonetheless, Wine Australia has issued a recommendation that, before exporting wine to China, wine companies should have their wines analysed for manganese content, although Australians do not add manganese to their wine and neither do winemakers in other traditional wine producing countries.

Australian vintners are not the only ones falling foul with the Chinese authorities. In 2013 the authorities in Xiamen destroyed 375 cases of Spanish wine because they contained more iron than norms allowed. Elevated levels of manganese led to a consignment of French wines being impounded, the Decanter magazine reported in 2013.

In view of these incidents, many suspect that using limits on substances like manganese or chloride to restrict imports is potentially a convenient way for Chinese authorities of getting around having to remove tariffs with the signing of free trade agreements while still protecting local industries.

In recent years China has shown an insatiable thirst for wine. China’s love of wine is growing at such a rate that it is expected to become the world’s largest consumer of wine by 2016. This is quite a jump for a nation whose per capita consumption of wine is significantly below global levels (perhaps less than a bottle per person per year) and where it’s still not unusual to have red wine served with soda.

To cope with rising demand for wine, China has been increasing its wine-growing area, thereby becoming the world’s fifth-largest producer in 2013, behind Italy, France, the U.S. and Spain, according to the International Wine and Spirits Research (IWSR), a London-based drinks research group.

But China still needs to import huge volumes of wine. Imported wines have risen rapidly – by more than seven times between 2007-2013 – pushing up their share of the domestic market to 18.6 percent, IWSR says.

According to IWSR data for 2012, French wines represented the bulk of wines imported by China (about 45 percent of total). Wines from Australia (ranked second), Spain, Chile, Italy and the U.S. combined almost equalled that amount.

Especially, for Australian wines, China has become a major export market. In terms of volumes, China is Australia’s fourth most important export market (36 million litres in 2012), behind the United Kingdom (238 million litres), the U.S. (173 million litres) and Canada (51 million litres).

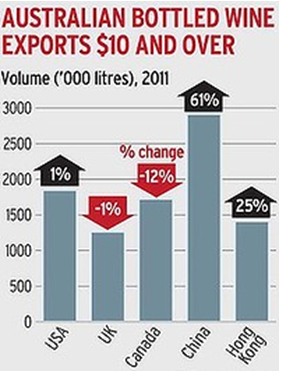

However, in terms of value, China is Australia's largest export market for wine over AUD 10 a litre. According to data released by Wine Australia, Chinese imports in the AUD 10-plus category (EUR 6.80) in 2011 almost equalled that of the U.S. and British markets combined.

This figure does not include Hong Kong which managed to import more wine in this price bracket than the entire British market.

More importantly even, most of the growth for China came in the premium-priced AUD 20 to AUD 50 price bracket, where profits are significant.

Although China will be seeking to import wine to cover its consumption in the coming years, the majority of wine the Chinese will drink in the long run will be made in China. And that’s just the way Chinese authorities like it. Viz their resorting to bans.

Funnily, Chinese investors, who have been buying up wineries all over Australia in recent years, seem undeterred by their country’s ban on manganese-rich Australian wines. In Australia’s Hunter Valley, it has been claimed that every winery sale in the region over AUD 1.5 million (EUR 1.1 million) in the past few years has been to Chinese buyers.

What their reasons for these investments are remain unclear. At least in France, there is suspicion that winery purchases are often used to launder money. According to an article in TIME magazine, French anti-money laundering authorities, Tracfin, raised the alarm in 2013 over acquisitions of vineyards by Chinese and Russian investors through multiple holding companies. As the article says: “Buying a vineyard happens to be a useful way to launder money as paying in cash is not unusual and the price of wine is never fixed.”

There seems to be no stopping China from becoming a wine superpower: it has the domestic demand and obviously the money too.