Colonial Williamsburg: The birthplace of American beer

Historic brews | At Colonial Williamsburg, a 1.22-km2 (301-acre) “historic district and living-history museum” [1] in the heart of the small City of Williamsburg in the state of Virginia, history indeed comes alive … literally. As you stroll along painstakingly reconstructed residences, workshops, inns, and taverns dating from the late 18th century, interpreters and actors in period costumes recreate daily life from the time of the American Revolution (1775–1783), when such luminaries as the United States’ first president, George Washington, its third president, Thomas Jefferson, and its fourth president, James Monroe, walked the district’s streets.

Modern “time travelers” visiting Williamsburg and nearby Jamestown and Yorktown, all part of “America’s Historic Triangle”, can ride horse-drawn period carriages and watch craftsmen and women ply their trades, colonial-style. There are blacksmiths, gunsmiths, joiners, wheelwrights, weavers, wig makers, tailors, milliners, coopers, bakers, and, indeed, brewers; and one such craftsman is Frank Clark, Colonial Williamsburg’s Master of Traditional Foodways, who also does the brewing. Frank sat down for an interview with BRAUWELT International in a reconstructed kitchen and brewery from the 1790s. Over the course of an afternoon, the conversation, of which the following is a summary, turned not only to the beers he makes for The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation but also to the history of beer making in the region.

As Frank said, before the American Revolution, Virginia was, of course, still a British colony and its inhabitants were subjects of King George III. It all started in 1606, when an earlier British monarch, King James I, awarded the Virginia Company of London a vaguely defined region of North America, which was centered around what are now the York and James rivers. Eventually, the Company’s settlements evolved into plantations, in which, starting in 1619, slaves brought over from Africa raised barley, wheat, oats, beans, peas, carrots, cabbage, and turnips, as well as corn, pumpkins, and highly profitable tobacco — the last three crops being indigenous only to the New World [2].

Not surprisingly, the favorite tipples of Virginia’s early European inhabitants were the same that were also popular in Great Britain — mostly rum and cider, but also Brown Ale and Porter. In those days, the best beers in the colony were all imported from the mother country, usually from Bristol instead of London to shorten the sea voyage. Such brews, of course, were both scarce and expensive, which meant that only wealthy plantation owners and government officials could afford them. The ordinary colonists, by contrast, as well as the slaves, usually had to settle for something much less exalted and made locally.

Jamestown, home of the first brewers in North America

The oldest documentary evidence of beer making in the New World is from Jamestown, about 11.5 km (7 miles) southwest of Williamsburg. Founded by some 100 Englishmen of the Virginia Company on May 13, 1607, Jamestown is now recognized as the first permanent English settlement in North America. At the time, the area was a vast wilderness, populated only by native Americans. So before setting out from Britain, the men had to take all their worldly needs into consideration. And one necessity they may have overlooked on their initial journey was beer. Though there were many tradesmen among the settlers, not one of them was a brewer. Thus, once in the New World, they placed an advertisement back home in a London newspaper for two brewers to join them. Thinking ahead, they also planted a field of barley from seeds they had in store. By the time the next contingent of settlers, some 600 in all, arrived from England, in 1609, in nine ships, with livestock and provisions for a year, fresh barley was already waiting to be turned into malt and ale.

Malt in early colonial brews

The early brewers in the New World preferred to make their beers from imported raw materials, including barley malt and hops. When these were unavailable, however, they also used locally raised barley and wheat, often in combination in the same mash. In a real pinch, they even made beer with whatever alternative fermentables and flavorings they could get their hands on. Thus, we know of old colonial recipes that call, for instance, for cheap and readily available blackstrap molasses, a thick, dark syrup made from sugarcane grown in the West Indies that was also the raw material for rum. Molasses is rich in fermentable carbohydrates. In today’s terms, according to the United States Department of Agriculture, it consists of 29 percent sucrose, 12 percent glucose, and 13 percent fructose.

Another carbohydrate-rich colonial malt substitute was persimmon, a tree fruit in the genus Diospyros. Different varieties of persimmon grow all around the world but only one, Diospyros virginiana, is native to the eastern United States. It is inedible until ripe, but then develops plenty of fermentable glucose. The fruit was macerated and mixed with water at a ratio of roughly one to five and often fortified with some sugar and cornmeal. After 3 to 4 days of fermentation, the result was said to be clear, light-colored, and fizzy. Persimmon ale was especially popular among the colony’s indentured servants and the slaves who worked the plantations.

Another way to make scarce beer ingredients go further in colonial times was as a hot beer toddy, also known as a hot ale flip. One possible way to mix it was to “stretch” about half a liter (roughly 16 fluid ounces) of Brown Ale or Porter with two tablespoons of molasses, two eggs, and some grated nutmeg. Optionally, for an extra kick, the drink sometimes received five or more tablespoons of dark rum as well. Such a beer punch was consumed hot, heated with a hot poker, known in the colonies as a loggerhead. The poker was standard equipment in every proper colonial household. It was simply put into a fireplace until red hot and was also used to cauterize wounds [3].

Hops in early colonial brews

For hops, North American colonists used not only imported but also locally raised crops. One key confirmation can be found in a set of detailed hop planting instructions in a diary by Landon Carter of Williamsburg, written between 1752 and 1778 [4]. In his time, Carter was one of the richest men in Virginia and the cantankerous owner of about 500 slaves who worked his 200-km² (50 000 acre) plantation. As Carter explained it, “a rich, deep mellow, dry soil more inclining to sand than clay, is in general the fittest for hops. It produces strong & vigorous plants and a great quantity of hops & requires much less manure than poor shallow land … Therefore, choose the richest & best meadow grounds you have for hops, your choice should be govern’d by the goodness & depth of the soil without regard to low or rising grounds” [4].

Unfortunately, Carter does not tell us which varieties he planted on his “richest & best meadow grounds,” but it was likely a variant of Farnham, on old British landrace, so-named after a market town in Surry, southwest of London, where it was grown. Farnham was once the most common hop variety in England. It stands out for its very pale green bines and leaves, which fit Carter’s description perfectly: “The white vine [he means bine] produces the white hop both long & oval. The gray or greenish vine yields the large hop” [4]. Genetically, Farnham is a predecessor of the modern Whitebine hop varieties of the Golding group, which is why it would be legitimate for today’s brewers to use Golding hops for an authentic recreation of a colonial ale [5].

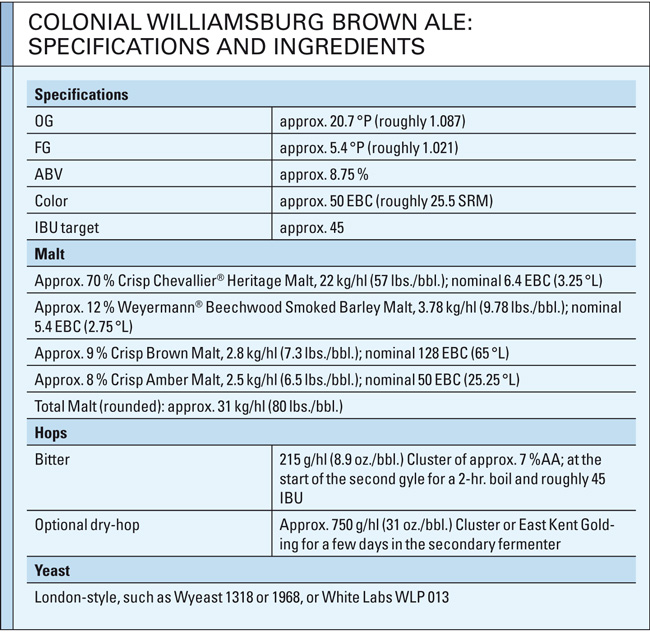

Another modern hop candidate for such a colonial beer might be Cluster, a variety considered a cross between an unknown English domesticated female and an equally unknown American wild male hop. It is well-established that, during colonial times, imported hops planted in the New World often hybridized with indigenous American wild species to form new varieties. Given Williamsburg’s location, the wild parent of the hops grown in and around the city could have been Humulus lupulus lupuloides, which happens to be the only one that is native to eastern North America. This is why Frank recommends Cluster as the hop to use in a modern recreation of the Colonial Williamsburg Brown Ale presented here (see recipe below).

Colonial Williamsburg Brown Ale

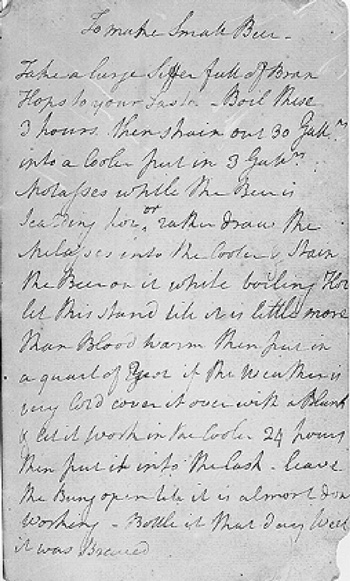

Because recipes from pre-industrial times use only vague measures for quantities –such as a handful, one pot, a large copper, or a large “siffer”– precision is not a requirement when following the recipe below. Rather, the selection of specifications and ingredients represent Frank’s best guesses, based on a careful consideration of many historical sources.

The brewing equipment and processes varied, too. After all, many colonial frontier settlements were places of scarcity and brewers had to make do with what was at hand. Vessels were usually made of wood and the most prized tub was a direct-fired kettle made of copper. Brewers might have had separate tubs for mashing, lautering, and wort collection, often stacked one on top of the other for transfers of the mash or wort by gravity; or they had multifunction vessels for several brewing steps. The recipe here is adapted and simplified so that it can be implemented in either a modern two-vessel brewhouse with a stationary mash or in a more elaborate brewhouse with slurry-pumping capabilities.

In the grain bill, the base malt choice is Crisp Chevallier® Heritage Malt. It is a modern, floor-malted re-release of a British heirloom barley that was first used in brews around 1820. Compared to many modern malts, it adds warm cracker and biscuit aromas to the brew. The Weyermann® Beechwood Smoked Barley Malt was selected to add just a bit of smokiness to the mash because, prior to the invention of pneumatic malting in the middle of the 19th century, virtually all malt was dried in direct-fired and, thus, smoky kilns. Such kilning also accounted for a very inhomogeneous modification and malt color, which ranged from perhaps ivory to almost black. Hence, the addition of some Crisp Amber Malt contributes toasty, biscuity, and slightly nutty notes. The addition of brown malt represents a nod to the standard malt used back then in most British ales, often just by itself. It was also likely exported to colonial Williamsburg. The Crisp interpretation of the malt, though no longer made the traditional way, contributes robust, roasty, and slightly coffee-like aromas, as well as a deep brown color. As explained above, the hop choice is Cluster; and, appropriately, the yeast is a London-type ale strain.

Though Frank has brewed this ale many times with period equipment, it is not for sale to the millions of visitors to Colonial Williamsburg because of the limited quantities. Instead, visitors can purchase an adaptation of this brew under the name of Colonial Williamsburg Old Stitch Brown Ale, made under an agreement by the local Alewerks Brewing Company.

Process

- In the kettle, bring the mash liquor to a boil. Because this recipe relies on a party-gyle process of two separate run-offs, without sparging, use slightly more than half the intended net kettle volume of your system. To determine the additional liquor (beyond half the net kettle volume), consider that 1 kg of modern grist retains about 1.7 liters of liquor (0.2 gallons per pound).

- Note that, in original recipes from the 18th century, the liquor-to-grist ratio was probably less than half of what it is today, because modern malting techniques and improved barley varieties have made brewing grains so much more extract-efficient.

- Use the hot liquor to pre-warm the mash tun or mash/lauter tun.

- Return the liquor to the kettle. The temperature should have dropped to roughly 75 °C (165 °F).

- Place one-half to two-thirds of the milled grain into the mash vessel and infuse with the liquor. Once the temperature has equalized between the grain, the tun, and the liquor, it should be roughly at 68 °C (155 °F). If needed, adjust it up or down with additional hot or cool liquor.

- Stir the mash vigorously for about half an hour.

- Spread the remaining milled grist over the mash, but without mixing it in. This is an old parti-gyle mashing technique called “capping.” It under-extracts sugars during the first run-off, but leaves more extractable sugars than would otherwise be available for the second gyle.

- Cover the mash to retain heat and leave it undisturbed for a one-hour rest.

- Lauter slowly.

- For the second gyle, bring about half the net kettle volume of liquor to a boil. Remember, the grist is already saturated with liquor from the previous gyle.

- Add the second batch of liquor to the mash, making sure that the mash temperature is roughly around 66 to 67 °C (170 to 172 °F).

- Let it rest for about 30 minutes.

- Lauter this gyle on top of the wort from the previous gyle.

- Boil the combined wort for two hours. In a wood-fired kettle, this generates plenty of caramelization and, unbeknown to brewers at the period, melanoidins from the Maillard Reaction.

- Add the bittering hop (Cluster or equivalent) at the start of the boil (first-wort hopping). Naturally, in the old days, all hops were added as cones but there is no reason why modern brewers could not use pellets.

- At the end of the boil let the wort cool off. Modern brewers can, of course, use wort chillers or heat exchangers to hasten the process.

- Pitch the yeast. In colonial Williamsburg, fermentation time varied greatly, depending on the weather. Modern brewers should probably keep the brew in the primary fermenter for about two weeks before transferring it off the sediment into a secondary fermenter. Do not bung either fermenter.

- Keep the brew in the secondary fermenter for about a week. Optionally, dry-hop it for a few days (with Cluster or East Kent Golding or a combination of both).

- Rack.

- In the old days, beer was packaged in casks or in bottles closed with corks that were often held in place by string or wire.

- Because the brew is fermented without pressure, it was common in colonial times to prime each bottle with 3 or 4 raisins or currants.

- Because this recipe results in a fairly strong “keeping” ale, its shelf life ought to be about two years.

Sensory evaluation (by Frank Clark and the author)

The color of this reconstructed Colonial Williamsburg Ale is deep chestnut to sepia brown with a creamy beige head. The nose perceives a fresh, yet rich and aromatic, molasses-like maltiness with a faint whiff of roastiness and smokiness reminiscent of old style direct-fired kilns. On the palate, this ale appears surprising light for a high-gravity brew. The taste is dominated by a mixture of chocolatey roastiness and an almost fig-like caramel sweetness. The biscuity finish is surprisingly dry, with a mild and lingering smokiness. Overall, this beer is very balanced and deceptively quaffable.

A collection of historical beer recipes from the end of the 18th century from north america can be found online on www.brauwelt.com/en.

References

- Colonial Williamsburg, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colonial_Williamsburg and Williamsburg, Virginia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Williamsburg (accessed 2021/09/06).

- Settlement Museum at Yorktown, https://www.historyisfun.org/learn/learning-center/what-did-the-typical-virginia-farm-look-like/ (accessed 2021/09/06).

- Hirsch, Corin: “Forgotten Drinks of Colonial New England: From Flips & Rattle-Skulls to Switchel & Spruce Beer”, Charleston SC, 2014.

- Carter, Landon: “The diary of Colonel Landon Carter of Sabine Hall”, 1752–1778, published by the University Press of Virginia, 1965, on behalf of the Virginia Historical Society.

- Wray, Edward: “The Farnham Whitebine Hop”, The Journal of The Brewery History Society, 147, 2012, pp. 17–22.

Keywords

Authors

Horst Dornbusch

Source

BRAUWELT International 5, 2021, page 307-311

Companies

- Cerevisia Communications, Williamsburg, United States