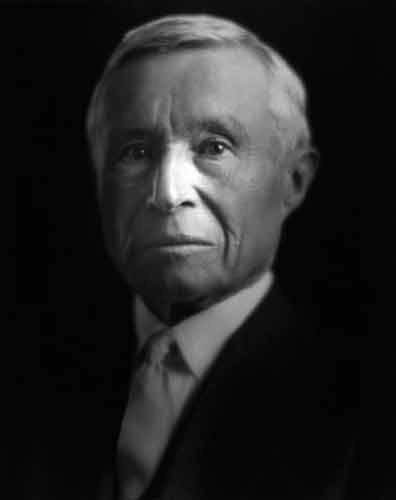

Giants of brewing history: Adolph Coors

From stowaway to hectolitre millionaire | Rarely have triumph and tragedy been so close in a brewer’s life as with Adolph Coors. Starting with virtually nothing as an immigrant in the USA, he opened a brewery in no man’s land, and built it – after decades of hard work – into one of the largest breweries in the world. However, he was never truly happy despite all of his success. In part three of our series, Günther Thömmes portrays the remarkable life of this giant of brewing history.

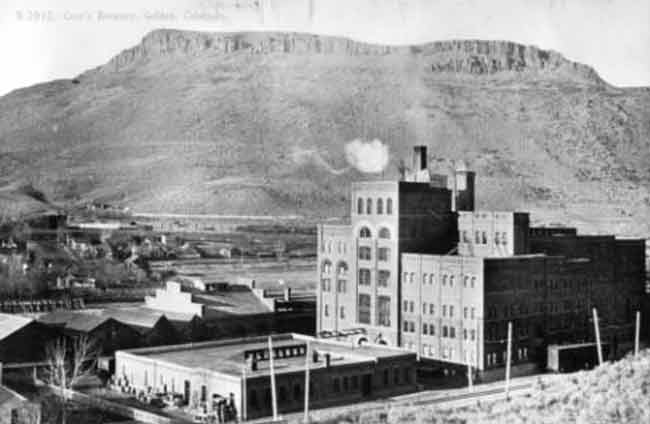

The brewery known as the Coors Brewing Company in Golden, Colorado, USA, with an annual output of over 15 million hectoliters, has been the single largest brewing facility in the world for many years. A more extreme contrast to its humble beginnings is hardly conceivable.

Adolph Hermann Joseph Kohrs (also, Kuhrs) was born in Barmen, Germany on February 4, 1847. Now a district of Wuppertal, at that time, it belonged to the Prussian Rhine province (with the city of Koblenz as the administrative center).

At the age of 15, the boy became an orphan when first his mother Helena and then his father Joseph died over a short interval, both in the year 1862. At that time Adolph was working as a brewer’s apprentice at Henry Wenkers Brauhaus in Dortmund. He worked as an accountant on the side in order to pay his tuition. As becoming a journeyman brewer, he remained with Wenker until May of 1867, after which he left and earned his spurs as a brewer in Kassel, Berlin and Uelzen.

Heading to America as a stowaway

Times were tough, and the political situation was troubled. Prussia’s wars against Denmark and Austria were not so distant, the German Confederation had dissolved, and Bismarck continued to show a penchant for aggression. America, too, had its fair share of fighting within its borders, with the Civil War having just ended three years prior.

In 1868, at the age of 21, the young journeyman brewer was threatened with being drafted into the Prussian army. In the hope that America – unlike Germany – had finally found peace, he evaded the military’s call by absconding to America. He wanted to seek his fortune there rather than in Europe, just as 5.5 million of his fellow Germans had done between 1820 and 1920.

He did not have the funds to pay for his voyage. Approximately 100 marks, or around 1000 euros in today’s money was required of emigrants at that time for a transatlantic crossing, so he simply snuck on board a ship as a stowaway in Hamburg. He was ashamed of this throughout his entire life. It was kept a secret by the family until 1970. Only after the death of his son Adolph Coors II was this part of the family’s history openly discussed and published.

The young man had the misfortune of being discovered in his hiding place and was given a choice: he could either earn his passage after arriving in New York City or be thrown overboard. The decision was easy. After a year of hard work, the debt for passage on the ship was paid and Adolph Kohrs was a free man.

From day laborer to businessman

He traveled west, looking for work in Chicago. There he worked as a day laborer, a brewer, a coal shoveler for steam engines, and for masons and stone cutters. He returned to brewing again when he was hired as a brewer at the Stenger Brewery in Naperville, Illinois. After three years there, he had amassed some savings and went to Colorado. There, in 1872, he was able to invest in a bottling plant. He was apparently a resourceful businessman because in less than a year he had become the sole proprietor of the company and was selling bottled beer, cider, wine and mineral water.

Kohrs, who in the meantime had altered the spelling of his name to make it seem more American – had brought his knowledge and understanding of the importance of good brewing liquor (water) with him from his homeland. So, he took the opportunity on Sundays, a day when he was not busy overseeing his business, to drive around the area looking for an optimal location for the brewery that he would eventually build.

The local water determined the site of the brewery

Coors finally found what he was looking for in Golden, near Denver, on a small river named Clear Creek – nomen est omen! The frontier town had only been founded fourteen years earlier, so it was an authentic part of the Wild West.

In Jacob Schueler he found a partner who increased his own capital of 2000 dollars ten-fold. At the age of 26, Adolph Coors had taken the first step towards the American Dream. But he had to be an optimist because Denver, with almost 50 000 inhabitants, already had seven breweries.

But Coors was an entrepreneur who refused to give up. He relied upon a strict work ethic, innovation and high quality from the very beginning. Two years before Colorado became the 38th state to join the United States (this took place on August 1, 1876), the “Golden Brewery” operated by Coors and Schueler began producing beer. It only took another six years before Adolph Coors had bought his partner out, making him the sole proprietor of the brewery. From this time forward, the brewery bore the name the “Adolph Coors’ Golden Brewery”.

He married Louisa Webber, the daughter of a senior employee at the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad Company. The family grew much in the same way as his wealth did. By 1888, Louisa had already brought seven children into the world, two of which died soon after birth. The young man who had arrived as a penniless immigrant on the shores of America in 1868 was well on his way to becoming a very prosperous man.

Several years later, around 1890, he had become a millionaire and one of the wealthiest residents of Colorado. Since the Coors family was travelling around the world for pleasure by that time, their last son, Herman Frederick Coors, was born during a family vacation in Berlin in July of 1890.

German brewers made pale lager popular in the U.S.

His beer, for which he invented the name “banquet beer”, stood out among the competition due to its light body, drinkability and wonderful, bright color. The soft water made this possible. Therefore, the resounding success of German-style pale lagers in the US can be attributed to Adolph Coors, along with several other German immigrants who opened breweries.

Coors chose to follow a completely different path than that of other large business owners in America during this time, i.e., those for whom the term “predatory capitalism” was coined: the Rockefellers, Vanderbilts, Astors, Carnegies and Morgans – almost all of these families had emigrated from Europe with as little means as Adolph Coors.

Coors allowed his employees to become members of a trade union, paid them decent wages and offered them longer breaks and more Haustrunk (a regular beer allotment) than other breweries.

Prohibition and World War I

However, by the end of the 19th century, the abstinence movement was already beginning to cast a long shadow. Coors did not fight them; instead, he invested proactively in other industries, such as porcelain and ceramics.

He expected a recession, but not full-scale Prohibition, which hit Colorado particularly early and quite hard. Four years before the rest of the USA, by 1916, he was forced to convert production at the brewery to “malted milk” and other non-alcoholic products. However, this was not his only problem.

From its founding until 1915, German had been the primary language in his brewery, just like in many other breweries and in US brewers’ associations. Adolph Coors even bought and promoted German war bonds – as long as the US did not get involved in the First World War. However, being German or even speaking the language of his home country became increasingly unpopular, if not outright dangerous.

The torpedoing and sinking of the RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915, finally spurred Coors on to cease his support of the German Reich and also caused him to switch the language in his company to English. From then on, his money flowed into American war bonds – just in time, too, because in the years that followed there were open hostilities throughout the country against everything that even slightly “reeked” of Germany, particularly after the United States entered the First World War in April of 1917.

Coors questions his own mass production

According to witnesses, Adolph Coors was the type of entrepreneur who believed in free markets, but he also always wanted the best for his employees. He saw himself as a craftsman, as a brewer, but not so much as an entrepreneur – and certainly not as a magnate. Given his simple background, Coors identified more closely with his workers rather than with the members of Denver’s high society.

As time went on, he became visibly more critical of his own products, to the point that he openly questioned the mass production of pasteurized beer as well as mass marketing. Adolph Coors took an increasingly pessimistic view of the industry’s development – and not only due to Prohibition.

However, he did not live to see the end of Prohibition in 1933. On June 5, 1929, at the age of 82, Coors fell from a window on the sixth floor of the Cavalier hotel in Virginia Beach, Virginia, where he was staying to recuperate from the case of the flu. He left a last will and testament in which he only specified that his hotel bill be paid in full and provided no further justification for his suicide. His brewery remained one of the few in the US that survived Prohibition.

His spectacular life story, the journey “from rags to riches” and his penchant for brewing beer as a quality rather than a mass product make him an exception in the history of brewing. Despite their father’s pessimistic predictions, his children continued to successfully run the brewery.