All things must pass

Magpie & Marten: Column | The past is fascinating. Modern brewing techniques do little to illuminate our previous efforts to make potable beverages from grain over the last 10+ millennia. We only see the end result of many gradual developments and extinct practices. The production processes common to almost every modern brewery, though widespread around the world, are not representative of the diverse methods that have existed over the entire history of brewing. Even though the laws of physics haven’t changed since they were set down by the Big Bang, there’s more than one way to coax fermentable extract from tiny, starchy, husk-encased grass seeds.

The astounding variety of brewing practices even as close to us in time as the 19th century – given the highly regional nature of beer production and the many thousands of breweries pocking the beer landscape at the time – were victims of the calamitous 20th century, when the unspeakable destruction of its first half and the aftermath in the second were not limited to people and property but also saw traditions extinguished to the point of forgotten obscurity. Many of them are worth remembering, if only for the sake of understanding our past, but also for the insight they might provide us now.

Quiet and roaring

Given the frosty, dreary time of year, a pot of hot tea-inspired winter musings might transport the mind back to a time in the latter half of the 19th century, when Queen Victoria made her headstrong relatives across Europe mind their manners, allowing peace to reign during a time of ‘quiet politics and roaring prosperity,’ as described by historian G. M. Trevelyan.

Lagers were only a Bavarian and Bohemian phenomenon; gose was drunk throughout the Harz in various forms and almost exclusively in Leipzig and Halle. Other variants on lost beers brewed with both malted and unmalted wheat could be found across the North European Plain. Lambic was a staple of Brussels, though Belgium brewed a diverse range of beers. Düsseldorf produced Alt, and Cologne, Kölsch, from a mix of grains and, unlike their earlier cousins, from hops as well. British and Irish ales were brewed in thousands of pubs. Scandinavia, Finland, the Baltics and their islands produced sahti and maltøl, among others. In Central Europe alone, the following were listed in contemporary sources as distinct brewing practices: Köstritzer, Saxon, Prussian, Franconian, Rheinish, Bohemian and Bavarian to name a few. For those interested in Europe’s extinct beers (and if one could afford to travel back then), it would have been a remarkable ‘Zeitreise’ (journey through time).

Here, there and everywhere

At the time, coolships would’ve been ubiquitous. Extremely shallow, wooden coolships made of Kiefernholz (pinewood) were the earlier form of these vessels and would have harbored yeast in their cracks and crevices. Even with metal coolships, there were still plenty of wooden vessels in a brewery not to mention fruit flies upon which yeast could hitch a ride. Prior to the application and implementation of Pasteur’s discoveries, every brewery, with their decades-old, or perhaps even centuries-old, equipment (mostly made of wood) would have been a microbial microcosm of ‘house flora’ unto themselves. Boiling hops in the wort was a common practice in almost every brewery by then. However, lambic brewers still allowed the α-acids in the hops to “age out” over three years before usage, since many of the microbes in their ‘house flora’ detest them. One might not think so, but lambic production is anything but a haphazard process.

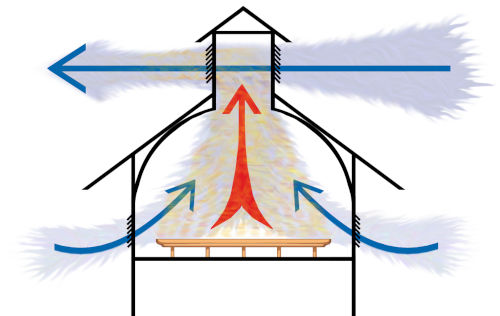

On this journey through time, one would no doubt notice that every brewery, not just those courting a wide range of microbes, employed a coolship. Almost all of these would have been installed in rooms with vaulted ceilings designed to prevent drippage and which were kept clean of dust and mold.

Because they were so widespread, one still finds coolships in breweries scattered across Europe. Due to their role in partially inoculating spontaneously fermented beers in Belgium, those new to brewing or unfamiliar with its history assume this was their sole purpose. Not so. One still sees them, or at least the louvered, peaked roofs where they once stood, in older breweries across the Continent and the British Isles.

Steamy but shallow

Upstream a hop jack removed the whole hops and downstream a Baudelot (falling film) chiller dropped the wort to pitching temperature. Coolships were recognized as a valuable tool between these two pieces of equipment, since brewers could leave the wort to ‘ausstinken lassen’ (let the wort ‘stink out’) prior to the actual chilling step. Thermal stress was reduced with a coolship, since, e.g., the Maillard reactions and Strecker degradation, quickly ceased. Of course, the post-boil isomerization that now occurs in a whirlpool didn’t take place in a coolship.

But the shallow nature of the vessel was the key to its primary purpose. Though the wort was relieved of undesirable volatiles, like DMS and Strecker aldehydes, after the boil, the brewer’s primary requirement at this stage was a sedimentation tank to remove the hot break and some of the cold break. The largest coolships held around 300 hl of wort due to the limitations of the surface area (~150 sqm). The angle of inclination towards the drain needed to be so slight that the hot break wasn’t drawn off with the wort. Around 4–8% of the total wort volume remained in the hot break material so it was often recovered in a trub press or centrifuge. The cold break was reduced by 15–25% if the wort was withdrawn at 65–45 °C. This value would increase to 30–40% if left overnight to cool down completely in winter. As mentioned in our previous column, the brewing season was limited to between Michaeli (29 Sept) and Georgi (23 April), and this was largely due to coolship usage but also to fermentation temperatures. Lambic brewers still follow this seasonal rhythm.

With the introduction of the more convenient pelletized hop powder accompanied by the whirlpool, coolships fell out of use mid-20th century. However, a whirlpool, unlike in a coolship, does not allow the undesirable volatiles to continue to vaporize and escape the wort. Thus, new equipment has been developed to fulfill this role, e.g., thin-film evaporators and stripping columns positioned downstream from the whirlpool. It must be said that coolships do not allow for as much thermal energy recovery as do the more modern wort chilling systems.

‘Coolships are cool!’

The European brewing traditions that moved across North America with the settlement of that continent did not survive in their entirety there either. Add Prohibition to an already volatile blend of factors, and one sees in this period a rather stinted and deeply stunted industry reemerging in its wake. The over-adjuncted, underwhelming, insipid beers of the giant conglomerates spread like a suffocating blanket of Kräusen over North America in the 1970s.

This blandness elicited a strong reaction: craft beer. One must say, quite laudably, craft invigorated the beer landscape by bringing back a number of traditional brewing practices to North America, though a few fell prey to the allure of the opposite extreme: the overreaction of over-hopped, under-attenuated, overly malty beer. That aside, craft has succeeded in making the US a much more interesting place to have a beer than it was 45-odd years ago.

Coolship usage has undergone a renaissance, and yet they are often misunderstood as vessels whose sole function is to induce spontaneous fermentation, which represents merely a tiny niche in their overall evolution. Thus, modern coolships are frequently misdesigned, being often too deep to carry out their true function as sedimentation vessels which also happen to allow indispensable vaporization of certain undesired volatiles in th

Keywords

history brewery equipment wort brewing methods

Authors

Christopher McGreger, Nancy McGreger

Source

BRAUWELT International 2026