The impact of the AB-InBev-Constellation deal on U.S. beer market

“We believe this transaction brings no change to the U.S. market,” AB-InBev’s CEO Carlos Brito told analysts when the deal was announced on 29 June 2012. Mark his words.

Several market observers beg to differ. As they see it, the deal could change things. For one, the price of imported beers could go up.

Traditionally, leading imports such as Corona and Heineken have cost more than mainstream domestic lagers like Bud or Miller Genuine Draft. But in recent years, because of the U.S.’ economic wobbles, import pricing has stayed flat, and the gap between the two segments has narrowed. The result has been weaker sales for the domestic brewers, because consumers don’t have to pay as much of a premium for the imported brand.

The way brewers like AB-InBev and MillerCoors responded to this was to drive efficiencies. As Jim Koch, CEO of Boston Beer, put it aptly in 2010: “The big brewers today in the U.S. have become very profitable by driving efficiencies at the same time as they’ve maintained prices in real dollars”, Mr Koch said. “That’s their business strategy right now: maintain healthy pricing and take costs out of their businesses, become more efficient. And that’s not a bad thing. They’ve become world-class efficiency experts.”

That’s why AB-InBev, for example, has been able to boost profits in the U.S. these past few years despite selling less beer.

It would certainly help AB-InBev’s domestic sales in the U.S. if Corona raised its prices. Corona is the sixth largest beer brand in the U.S. with 7.2 million barrels (8.5 million hl) sold in 2011 and a market share of 3.4 percent, according to Beer Insights, a trade publication.

In June 2012, Beer Insights wrote that in the off-premise AB-InBev’s average prices were up 2.7 percent in the period January through May 2012; MillerCoors’ were up 2.4 percent, Crown’s were “essentially flat” while Heineken USA’s were down by about 1 percent. Beer Insights concluded that “the big brewers are having a tough time pricing up their biggest brands”.

One way to force Crown Imports, aka Constellation Brands, to raise the prices of Corona and the other Modelo brands it imports, is for AB-InBev to charge Crown more.

Then Crown has two options. It can either pass that price increase on to consumers, or eat it itself, which would be foolish.

In effect, selling Modelo’s stake in Crown Imports to Constellation will prove a boon to AB-InBev’s profits. They could get more money per hl from Crown. And if Crown raises retail prices for Corona, that will give AB-InBev more room to increase the price of Budweiser and Bud Light without losing market share.

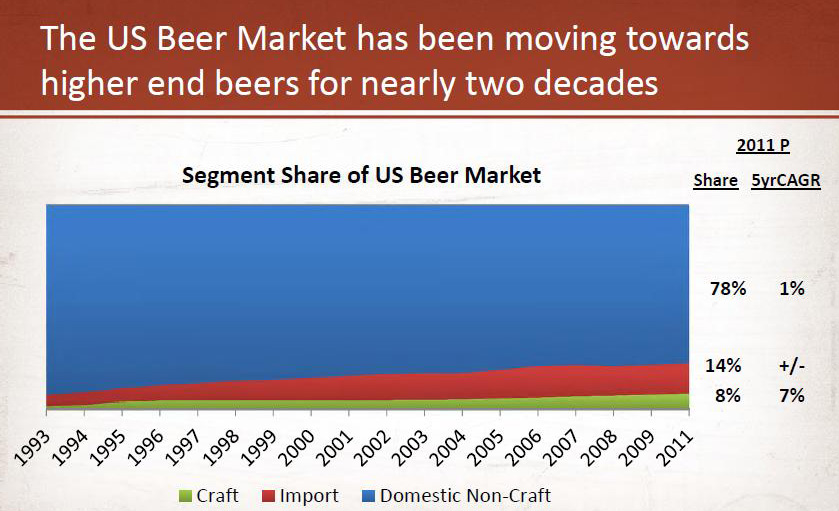

If Corona were to increase prices, craft brewers would benefit, too. Usually, craft beers are positioned in the worth-more segment, which is the aggregate of the Import, Super-premium, Flavoured Malt Beverage, and Craft/Specialty segments.

Despite their rising popularity, many craft beers have struggled with making ends meet. As Jim Koch put it in 2010: “We’re trying to figure out ‘How do we make Sam Adams and craft beer in general more desirable, even if it means making much more expensive beer [because we have such a high cost base – my addition]?’”

I was reminded of this when the now-defunct Michigan Brewing Company’s assets were sold at an auction in June 2012. The auction generated up to an estimated USD 1 million to satisfy debts to a Detroit-area creditor.

MillerCoors has purchased all brewing equipment (50,000 barrels capacity) and brands for an undisclosed sum, U.S. media reported.

As the story goes, Michigan Brewing Company (MBC) founder Bobby Mason lost control of the 9500 barrel beer company (volumes for 2011) when he failed to make payments on financial obligations.

Many of those obligations were related to loans Mason took out to repay previous loans, including USD 4.1 million in high-interest loans taken out over 22 months.

In other words, MBC overinvested and could not repay the loans. That’s a fate that probably also befell the 12 U.S. microbreweries which closed during 2011 and the 13 micros which went down in 2010 (according to the Brewers’ Association).

Microbreweries the world over struggle to run profitable, albeit high-cost operations as they try to keep up with rising demand while putting their beers on tightly packed beer shelves. There is no point in their flexing their muscles and saying that they can take on the big brewers. If the big guys keep prices down, the craft brewers will be first to turn up their toes and die.

So let’s hope that big brewers and importers in the U.S. show some business sense and raise beer prices overall.