Mishaps, missteps, and misfortune

In January 2014, five German brewers were fined a total of EUR 106.5 million for collusion in 2006 and 2008. Several more are under investigation by the Federal Cartel Office. Strangely enough, Germans still enjoy what must be the lowest prices for beer in Europe. Given that retail prices have actually declined over the past decade, many wonder what the real purpose of the beer cartel was since it failed to achieve a cartel’s primary goal.

The story so far. On 13 January 2014 the German trustbusters issued fines against four national brewers, a regional brewer and seven executives for illegally colluding to raise the price of beer. The brewers rapped included family-owned Krombacher, Bitburger, Veltins, Warsteiner and Barre. All had their penalties reduced for cooperating with the probe.

“Our investigations have allowed us to prove there were agreements between the breweries based mainly on purely personal and telephone contacts,” Andreas Mundt, President of the German Cartel Office, said in a statement.

“The price increases agreed for draught beer in 2006 and 2008 were in the range of EUR 5 to 7 per hl,” Mr Mundt said. “For bottled beer a price increase was discussed in 2008 that should have led to an increase of EUR 1.00 in the price of the 20-bottle case.”

Although involved in the cartel, AB-InBev escaped being fined because they had turned themselves prime witness and helped trigger the whole investigation, the anti-trust watchdog said.

At the time of writing, a probe into two other major and four regional brewers continues. The majors are widely assumed to be Germany’s biggest brewer Radeberger and Carlsberg’s German unit Holsten. According to rumour, Radeberger has refused to settle with the Cartel Office as their fine is estimated to be EUR 100 million, which means their case could end up in court.

How things will turn out for Carlsberg-Holsten is anybody’s guess. Fines for collusion in Germany can be up to 10 percent of a company’s turnover. However, in the case of foreign-owned companies like Carlsberg-Holsten, it could amount to several hundred million euros (or 10 percent of the Carlsberg Group’s 2012 turnover minus a discount), following a ruling by the German Federal Court last year which said that the parent company’s turnover should be taken into consideration too when issuing fines. But obviously, the Cartel Office first has to attest any wrongdoing to Carlsberg-Holsten.

With investigations into the beer cartel still on-going, total fines could ultimately reach a new high for food industry cartels in Germany. In comparison, eleven manufacturers of confectionery were fined EUR 60 million (USD 80 million) in 2013 for illegal price fixing. Also last year, 22 flour mills were penalised EUR 65 million over accords. The highest fine for collusion to date was slapped on three coffee manufacturers in 2010: EUR 160 million (USD 211 million).

But whatever sum the Cartel Office will force German brewers to own up to eventually, it will be small fry compared to the hefty punishment levied on Dutch brewers Heineken, Grolsch and Bavaria. In 2007, European regulators whacked them with a total of EUR 273.7 million for price fixing in the Netherlands in the late 1990s. In terms of volume, the Dutch beer market is only a quarter of the German, yet Heineken alone had to stomach about EUR 200 million which would have irked them lots as rival InBev went scotch free. Like in Germany now, the then InBev had provided decisive information about the cartel under the European Commission’s leniency programme.

All things considered, it’s hardly surprising that the four major German brewers decided to quietly settle with the Cartel Office and contritely accepted their fines. Insiders reckon that the fines were EUR 40 million for Bitburger, EUR 27 million for Krombacher, EUR 26 million for Warsteiner and EUR 14 million for Veltins. These sums will put a dent into their marketing budgets this year, ranging anywhere between EUR 10 million and EUR 70 million, and could force owners to forego their profits. In early January this year, the German business publication Manager Magazine put Bitburger’s annual profits (EBT) at EUR 50 million, which underlines how contrite they must be having been caught red-handed.

A double whammy to diddling executives

Equally severe are the fines for those individuals who negotiated the price fixings. They can amount to their annual salaries. Also worrying to them are cartel damage claims filed by the victims, in this case other brewers or consumers. Working out the financial pounding they may receive requires no degree and accounts for why executives often scramble to become whistle-blowers as soon as they hear the watchdogs bark in the distance. Insiders say it was a former AB-InBev manager in Germany who got the whole investigation rolling for fear his current company’s Directors & Officers insurance would not cover his personal fine. When hearing about his involvement, his previous employer AB-InBev would have been all for it for him to turn whistle-blower, considering that the foreign-owned AB-InBev would have faced the same terms of a fine as Carlsberg does.

Cynical observers have argued that cartels these days are commoner than anyone thought and that the fuss the Cartel Office kicked up will die down as soon as the watchdogs pick up another foul stink elsewhere. This may well be true. Lawyers certainly seem to treat cartels like any other business opportunity that has gone belly up. The legal website juve.de actually boasts that a German partner in AB-InBev’s global law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer specialises in representing prime witnesses in cartel proceedings. However, the German beer cartel is special. Not as in “precious special” but as in “weird special”. For one, it defies logic. The price hike was effectively diluted by increased promotional activity. For another, everybody involved ¬ – the brewers, the trustbusters and the media – employed some very, ahem, strange tactics, which made several industry observers I spoke to shake their heads in disbelief. Especially the Cartel Office and the media did not exactly cover themselves with glory in the hunt. If these things do not make the beer cartel special and worthy of deeper scrutiny – what would?

News that German brewers were involved in a beer cartel already broke in August last year and caused quite some consternation among pundits. A few, like this publication, wondered why Germany’s major brewers would risk being fined for cartel shenanigans and price fixing, while they put good money into retailers’ grubby hands so that these could sell even more of their beers on super-saver offers?

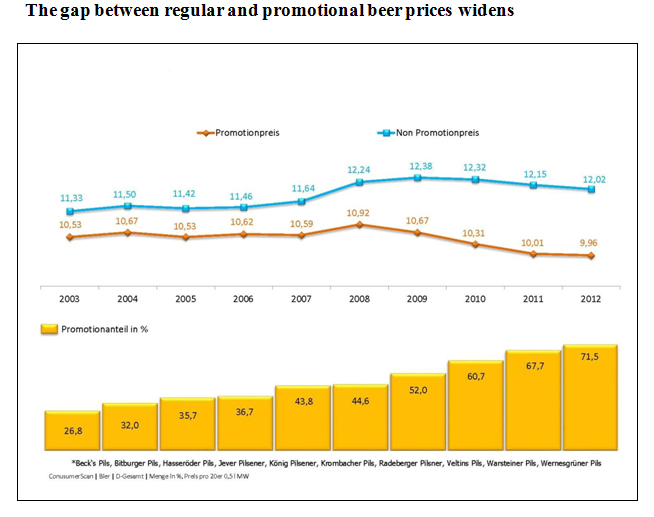

Fact is that, over the past decade, the volume of beer sold on offer for less than EUR 10.00 (USD 13.70) per crate (that’s 20 bottles x 0.5 litre) by major German pils brands has risen from 27 percent to about 70 percent.

All of Germany’s major so-called premium beer brands have been affected by the retailers hyperactively dumping prices. At any time you can find a crate of a major brand for EUR 9.99 or less. The best deal so far (December 2011) was a crate of Veltins beer plus some batteries plus a six-pack of something else at a supermarket for EUR 12.00, which translated into EUR 4.51/USD 6.00 for the beer itself.

Not that this kind of promotional activity came cheap to the brewers. Consider it a given that the retailers will not sacrifice their own margins. Therefore, it’s highly likely – although I have no proof for this – that the brewers, one way or another, subsidised these special offers. As one insider told me, contracts between the supermarket chains and their suppliers may include 50 different kinds of kick-backs, which the retailers can use as they deem fit.

Because German brewers have long put volume over value, beer retail prices are nominally as low as they were 20 years ago. If adjusted for inflation and VAT, they have almost halved during this period. I cannot think of any market, except perhaps for a few emerging markets, where beer is as cheap as in Germany’s off-premise channel.

Nevertheless, ultra-low beer prices have not stemmed the decline in German beer consumption. Between 1993 and 2012 beer consumption dropped 25 million hl or 23 percent. It declined by another 2 percent in 2013 or almost 2 million hl. Which makes you wonder: has it declined despite these low prices or perhaps because of those super deals? Beer may be cheap and cheerful but that’s not the same as saying that it is still aspirational.

All in all, German brewers for twenty years have had to contend with twice- reduced returns: in margins and volumes. The sad conclusion is that this has been all of their own doing.

The last time the German beer market witnessed a significant hike in beer prices was in 2008 – and this only came about, as the Cartel Office claims, because brewers rigged the market. Of course, any brewer going alone with price rises might as well commit suicide because he will immediately be punished with reduced volume sales. When AB-InBev barged ahead last year and put up the price of Beck’s, without other brewers following suite, they were socked by their consumers and sales of Beck’s declined by an estimated 193,000 hl year-on-year. Upon hearing that AB-InBev’s German chieftain Chris Cools, 46, had resigned in October 2013, quoting “personal reasons”, AB-InBev’s competitors only tapped their noses.

This episode shows that imposing higher beer prices on the German beer market is riskier than jumping out of an airplane without a parachute. Still, this does not explain why German brewers had to set up such a sprawling cartel, involving half a dozen major players, just to make sure that desperately needed price increases were not countered by others sitting on their hands. Why indeed? Therefore, many concur, German brewers deserve to be fined. They deserve to be fined not only because they acted against the law but because they acted like amateurs when organising their cartel. Let’s be frank, if I were to set up a cartel, unlikely though it is, I would take my clues from “The Godfather”. That’s why I would only do it with two of my most trustworthy competitors in order to minimise the risk of leaks. Robust cartels don’t function along the lines of “the more the merrier”. On the contrary, in the case of cartels it’s rather the “more the chattier”. This basic rule anyone could have gleaned from reading a few pages of “The Godfather”.

The trustbusters’ mysterious ways

No doubt, rooting out market riggers with fines benefits competition and assuages a self-righteous populist mood of “the law is the law”. But this does not mean that the German anti-trust enforcers’ tactics in sniffing out and punishing culprits are above reproach. The American way of trustbusting – which combines hefty fines with the promise of immunity for whistle-blowers which is increasingly being followed across the world, may irritate our innate sense of justice because it’s such a blatant “the end-justifies-the-means” affair. Yet luring cartel members with zero sentences if they grass on their accomplices seems to produce results. Without the whistle-blowers the regulators would not have been able to turn up wrongdoing as they have in recent years.

What many cannot understand, though, is why the whole process has to be so intransparent – not just for the scandal-loving public but for the accused themselves? To press further, why does the Cartel Office move in such mysterious ways? Why, for example, does it offer varying discounts on fines to the accused – 50 percent if you cooperate in the investigation, 10 percent if you settle with the Cartel Office out of court – as if they were haggling over the price of a carpet in a bazar? Moreover, why do the accused have to face a lengthy court case, costing them big bucks in lawyers’ fees, if they think the Cartel Office’s accusations have no merit?

Many of these points were raised by the regional brewer Barre, a 150,000 hl company located in Lübbeke, half way between Dortmund and Bremen. Barre was among those brewers who decided to settle with the anti-trust enforcers. Shortly after the Cartel Office’s statement, the owner Christoph Barre went public and complained how he had been put over a barrel by the regulators. These are my words, not his. According to him, his brewery and a few other regional ones weren’t among those initially investigated by the Cartel Office. The watchdogs only began to crowd in on Mr Barre early last year after one of the prime witnesses in the case had testified that he had informed the smaller brewers of his company’s imminent price hikes in the course of two committee meetings of their regional brewers’ association in 2006 and 2007. Because of this testimony, which is emphatically contested by all the smaller brewers, the Barre brewery was charged.

Backed by many documents and testimonies, Mr Barre tried to prove to the Cartel Office that his own price increases had not come about by virtue of any agreement with his competitors, nor were they influenced by his competitors’ hikes. Unfortunately, all this failed to convince the Cartel Office. So rather than push for a lengthy court trial, which could have gone on for years and would have cost his company several hundreds of thousands of euros with an uncertain outcome given the conflicting testimonies, he decided to enter into settlement talks with the Cartel Office. As he says, these talks were all about bargaining over the sum of the fine and not the accusations themselves.

To ward off further economic hardship from his company, Mr Barre in the end decided to plead guilty, which was the prerequisite for the EUR 100,000 fine offered to him by the regulators. It still annoys Mr Barre that the unpredictable financial risks of a trial made him follow reason and act against his judicial convictions. Besides, he is thoroughly upset by the trustbusters’ narrow view of what actually constitutes a cartel. According to Mr Barre, he is already in deep waters with the watchdogs should he happen to be in the same room with other brewers and accidentally overhear a salesman say that his company will raise prices. In order to stay on the right side of the law any eavesdropper should immediately report this salesman to the Cartel Office. How realistic is this, he wonders? More likely, brewers’ get-togethers will soon resemble a congregation of Trappist monks for fear the regulators’ snitches are hiding behind the curtains.

If, in view of actually falling retail prices, the German beer cartel looks like a botched affair it is because of cut-throat competition. Through concerted – but still illegal – price hikes brewers may have tried to make up what they lost before. Unfortunately, through their promotional activity they then, bit by bit, relinquished their “successes” to the retailers.

To get out of this vicious circle, “perhaps in future the Cartel Office should determine the price of beer in discussions with the retailers and without consulting the brewers“, Herbert Latz-Weber, the editor of the drinks blog, infodienst.de, griped recently. A window of opportunity will open up soon during the carnival season when no one cares how much they pay for a beer, he added. On a serious note, he worried that all honest brewers now had to suffer because of the bad reputation of the whole industry, where too many had forgotten to play by the rules of the “honourable merchant”. “Too many brewers still put volume over price”, Mr Latz-Weber complained. “Hopefully German beer can maintain its quality. But quality has a price. This is what consumers and retailers have to learn”. Well, Mr Latz-Weber: From your mouth to God’s ears!

Conspiring against smaller competitors

However, there is one aspect to this whole sad state of affairs which no one seems to want to pay any attention to: it’s called “killing off competitors”. What the scandal over price fixing has managed to push into the background is the fact that since 2008 Germany’s major brewers have refrained from raising prices. Did they do this for altruistic reasons, or because their money bin was filled to the brim? Hardly likely. Their restraint may not constitute an illegal cartel, let alone a conspiracy. Nevertheless, even if it was merely a silent accord, it still had fatal consequences. It helped consolidate the market the brutal way. It squeezed many of smaller brewers out of existence. Whereas before, brewers would have taken over smaller competitors in order to increase their market share, German brewers had learnt it the costly way that mergers and acquisitions don’t get them anywhere in an overall declining market.

Many would have remembered the takeover of Germany’s Brau + Brunnen Group by Radeberger in 2004. Radeberger, then ranked third and producing 8.5 million hl beer, took over Brau + Brunnen, then ranked fourth and producing 8.0 million hl, for EUR 350 million plus debt and pension obligations. In 2012 Radeberger Group sold 12 million hl beer. In effect, over the course of eight years Radeberger has lost 4.5 million hl in sales volumes, yet managed to defend market leadership. This would have taught all the others the lesson that without having to engage in complicated mergers and acquisitions they could maintain or even grow market shares for as long as they absorbed rising costs and continued to offer beer at incredibly cheap prices, all the while the smaller players wrestled for life or death.

One of the major casualties of this self-imposed price constraint was Oettinger, Germany’s third-ranking brewer and biggest producer of private label and cheap beers. Between 2008 and 2013 the privately-owned Oettinger had to sacrifice about one million hl in beer volumes. All too often Oettinger’s beers did cost as much as a national brand on promotion. Presented with such a choice, many shoppers went for the more aspirational brand instead which they found at their local discount retailers. Oettinger’s beers are only available in the national supermarket chains, which lost a lot of traffic in recent years to the discounters.

As one can image, there is no love lost between Oettinger and the rest of the German brewing industry. Many begrudge Oettinger’s owner Dirk Kolmar his success in wooing spend-thrift consumers and his cavalier attitude to membership in trade associations (he refuses to join but indirectly enjoys the profits of the industry’s lobbying efforts).

While Oettinger may have been able to compensate its domestic volume declines by revving up export sales, plenty of smaller brewers have not been so lucky. Between 1993 and 2012, over 110 breweries with an output between 100,000 hl and 1.0 million hl had to shut down. In view of the fact that beer consumption is forecast to continue to decline by an average of 2 percent per year, anybody can work out on the back of a napkin how many more brewers will have to turn up their toes before the majors reverse their pricing policy.

Alas, this is an area the anti-trust watchdogs won’t nose out. As their investigation is mainly limited to what they consider “hard-core cartels” to the disadvantage of consumers, by which they mean agreements on prices, sales quotas and the distribution of markets, they will – by default – turn a blind eye on other more insidious tactics: the stifling of smaller competitors by lowering retail prices of beer even further.

If, in years to come, more brewers bite the dust, the trustbusters will merely consider them collateral damage. In the Cartel Office’s own logic, a broad oligopoly is the best precondition for optimal competition in an industry. Which leads me to a crucial question: how many players would the Cartel Office consider a "broad oligopoly" in the brewing industry? I’d say: two handfuls of strong – albeit easier-to-control – companies. At present, the combined market share of the top ten brewers is roughly 50 percent. This shows the consolidation of the German brewing industry still has some way to go before the Cartel Office’s goal has been reached.

It’s hard to fathom what consumers will make of this scandal. The media were not exactly helpful in presenting them with the full picture. Rather than tell their readers or viewers that yes, there was a beer cartel, but beer prices nonetheless are at rock bottom, all they did was to fulminate how consumers had been cheated by the brewers. Some media outfits did not even think twice about spreading the figure of EUR 440 million that the brewers allegedly had made in extra profits (!) from their price fixing agreement. This questionable estimate, put out by a consumer watchdog, was allowed to make the media rounds until it was refuted by Mr Mundt of the Cartel Office himself in an interview in the German tabloid BILD on 17 January 2014.

By consensus, media say that brewers this year will pass their fines on to consumers by raising beer prices. That may well be the case. But rest assured that brewers will not give up their old habit of whittling away any gains from price hikes through their bad habit of near ubiquitous price promotions. Also trust the all-powerful retailers to make sure that beer remains their door-opener of choice.

What lessons are we to draw from the above? A German brewer once told me: “Price competition is a growth drug in young and hungry emerging markets – but it’s like assisted suicide in mature markets such as Germany. If sales volumes do not grow, the value of the brand has to grow. Anyone who does not understand this and does not draw the necessary conclusions from this and raises prices will not survive.” If German brewers had not worshipped the “Volume God” they would not have needed a cartel to raise prices – all the while counteracting it through increased promotional activity.

This underlines what Prof Peter Kruse, an expert in organisational psychology at the University of Bremen, once said of the German beverage industry: “Industry intelligence is reflected in the difference between the selling price of the manufacturer and the retail price. In this respect, the German beverage industry seems to have the least systemic intelligence.”

Rather than set up an illegal cartel, German brewers should have taken their clues from AB-InBev in the United States. Although AB-InBev lost 17 million hl in sales volume in the U.S. between 2008 and 2012, they continued to hike prices from USD 110 per hl to USD 126 per hl, thus growing their EBITDA from USD 4.7 billion to USD 6.1 billion in the same period. Other brewers did the same.

Did the U.S. anti-trust watchdogs smell a rat? No. Because it’s standard business practice, dictated by economic logic, to raise prices. You don’t have to resort to illegal tomfoolery to do so.