Brewers hope to tap the dividend of political stability

It’s good to know: should you plan to travel around the DR Congo by truck (some reckless tourists seem to do just that), pick a truck carrying bags of something soft like peanuts because sitting on top of them can be quite comfortable. Beer trucks are not.

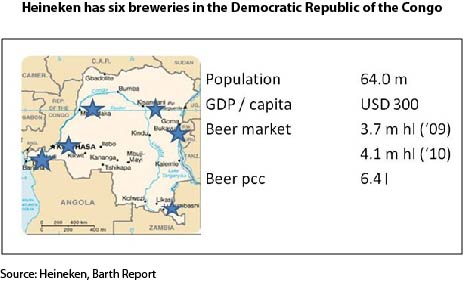

To international brewers the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), formerly known as Zaire, is a country of immense potential. With a land area spanning two-thirds of the European Union and a widely dispersed population of an estimated 64 million or 66 million people, of which one-third live in urban centres, like the capital Kinshasa, which itself is said to be home to about 10 million people, the DRC has been mostly known for its extraordinary agricultural and mineral resources and for the extravagances of its dictator Mobuto Sese Seko (1930-1997).

The country’s two brewers, Heineken (Bralima) and Castel (Bracongo/Brasimba) have had to show great perseverance over the past twenty years. Although the country is potentially one of Africa’s richest countries and one of the continent’s key engines for growth, it has been ravaged by a conflict which began in 1996 and which could be termed Africa’s world war even though it sadly received little sustained attention from the rest of the world.

The Congo war pitted government forces, supported by Angola, Namibia and Zimbabwe, against rebels backed by Uganda and Rwanda. Despite a peace deal and the formation of a transitional government in 2003, people in the east of the country still remain in terror of marauding militia and the army.

The DRC’s beer production figures are indicative of the country’s tragedy of war and poverty. In 1989, beer production was 3.1 million hl according to the Barth Report. It dropped to 1.5 million hl in 1996 when the conflict started and stood at 1.4 million hl in 2001.

While the country is largely at peace, the situation remains fragile. The socio-economic conditions in the country are dire, says the World Bank. The country’s infrastructure was largely destroyed during the conflict. Despite progress over the past five years in political and economic reforms, many communities live in deteriorating conditions, with little access to markets for purchasing supplies or for selling their produce, and poor access to public services.

Nevertheless, market leader Heineken, with an estimated market share of 65 percent, plans to invest EUR 400 million in its local unit Bralima over the next five years, it was reported in September 2011. Bralima operates 6 breweries across the country., while Castel has 5 (and one under construction).

In recent years beer production in the DRC has risen steadily: from 1.6 million hl in 2005 to 4.1 million hl in 2010 (Barth Report). This had persuaded Heineken to build a brewery in Lubumbashi in the DRC’s southeastern corner near Zambia. Lubumbashi is the DRC’s second-largest city and its Katanga province is a rich mining region, which supplies cobalt, copper, tin, radium, uranium and diamonds. The brewery was opened in 2008 and has a capacity of several hundred thousand hl.

On 7 September 2011 Hans van Mameren, Bralima’s Managing Director, was quoted as saying that the DRC’s outlook was positive despite uncertainty hanging over the general elections scheduled for 28 November 2011, as economic growth looked robust and any boost to infrastructure would see new markets open rapidly.

Bralima, which has been majority-owned by Heineken since 1986 (95 percent), has been operating in the DRC since 1923 and makes the country’s most popular beer, Primus.

Mr Mameren said EUR 250 million would be spent on renovating the original brewery in Kinshasa and building a new one 40 km away. Another EUR 150 million will be used to buy equipment and improve other breweries across the country.

Due to lack of infrastructure, Heineken’s breweries mostly serve local markets. If beer has to travel hundreds of kilometres by road or river to reach its destination, that pushes up the price to extremely high levels. A 0.75 litre bottle of Primus in Kinshasa may sell at USD 1.50 but the further away the higher the price.

Although DRC’s business climate is fairly hostile and tax is as high as 40 percent, Mr Mameren believes the nature of the product protects Bralima from the worst excesses of corruption and government hassle.

"We’re producing the cheapest luxury in this country; if there was a situation where there was no beer, the population would be very surprised, to say the least," Mr Mameren said.

Authors

Ina Verstl

Source

BRAUWELT International 2011