The laws of nature and non-alcoholic beers

Magpie & Marten | Dear readers: The following discussion continues one we started in our previous column in the print edition of BRAUWELT International, which is about non-alcoholic beer (NAB) and how it differs from normal beer.

One might imagine that beer in Western Eurasia, being the fermented extract of enzymatically modified cereals, hasn’t changed all that much over the millennia since humans domesticated the self-pollinating grasses of the Near East. What we mean by this is that although technology has advanced – instead of pots and wood, it’s now copper and stainless – unwaveringly, since its inception, beer has remained a fermented beverage obtained from the partially degraded endosperms of cereals. The malted grain extract itself has usually consisted of barley or some form of wheat. At times, even other cereals, such as oats or, the outlier amongst cereals, rye (a non-selfer, which came to Europe as a weed) has been utilized.

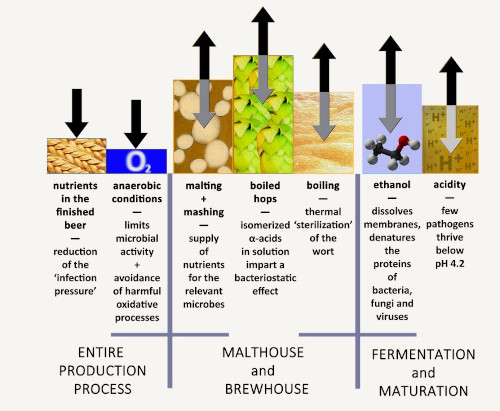

This is true in spite of the fact that various other ingredients have been added to beer over hundreds of centuries by brewers in many cultures to effect certain changes in the final product. Some ingredients, like dates or grapes, were used to flavor the beer in Bronze Age Mesopotamia, Egypt and around the Eastern Mediterranean and were otherwise propitious, given that sugar-loving yeasts were present on their skins and these fruits contained simple sugars to get the yeast going. Early European brewers sometimes added medicinal herbs, like meadowsweet, or even hallucinogenic plants, such as henbane, no doubt for ritual purposes. The unique innovation of early European brewers, however, was to complement their fermenting grain juice with plants that provided a modicum of defense against bacterial wort/beer spoilers. Prior to the adoption of hops, Northwestern Europeans, for example, made use of the small, not-so-pleasing sour cherries as contributors of simple sugars, yeast, acidity and polyphenols. In fact, many polyphenol-rich plants have been employed in beer over the centuries in Europe for their preservative properties, bog-myrtle (Myrica gale), being the most prominent herb in regions along the North Sea and Baltic coasts. Lambic brewers now employ hops, but they are aged because they’re still only interested in their polyphenol content. However, the one-two punch of fresh hops, i.e., with their polyphenols AND iso α-acids, boiled in the mash or wort, impedes the growth of beer spoilers and other undesirable microbes. This ensured their rise to prominence, first, in Slavic Europe where they were domesticated and where, being away from the coast, bog-myrtle doesn’t grow. Thus, hops became an essential ingredient in modern beer, as their usage moved west across the ‘beer belt’ to the British Isles. Just because we live in a more modern age than these Iron Age and medieval brewers, this doesn’t mean we’re free of the laws of nature as studied in the fields of microbiology, biochemistry, physics, etc. Brewers of NABs should not discount the contributions of their elders to the field of brewing, among them the boiling of wort with hops, for keeping their beverages safe (refer to the diagram).

The presence of microorganisms

So, if much has remained the same, except for flavorings and supplemental ingredients, what has changed in beer production since the dawn of modern brewing in late medieval Europe? One important and fundamental parameter is the presence of microorganisms in the finished product. Every beer container up until the advent of metal casks/kegs, glass and pasteurization contained microbes. Older beer styles still do, whether they only contain brewers’ yeast, such as in cask- or bottle-conditioned ale and weissbier, or a mixed set of microbes, as in Flanders red, oud bruin and lambic. For any of these beers, this isn’t a curse but rather a blessing.

Since the dawn of brewing, brewers have followed these laws of nature as summarized in the accompanying diagram, without really knowing it, because they ‘naturally’ occur. Generally speaking, if one is diminished or ignored, by the very nature of the process, the others tend to compensate, e.g., without the benefit of iso α-acids, for instance, the acidity, ethanol and/or polyphenol content will usually rise or the supply of nutrients in the beer will be more thoroughly diminished, either on their own through microbial activity or through trial-and-error additions or processes by brewers. Otherwise, the time one could keep the beer declined dramatically. Over approximately 130 centuries of beer production, the mixed microbes or brewers’ yeast, as the case may be, always remained in the finished product. This is one reason the imbibers of beer have always been protected from pathogens. What do the microbes accomplish? Looking at the diagram, they consume all the nutrients accessible to most microbes that can survive in beer; they likewise keep oxygen out by utilizing it and releasing carbon dioxide while also lowering the pH and releasing ethanol. Only in one century – the most recent one – have these microbes been removed or alternatively eliminated from beer.

The production of non-alcoholic beers

In the production of NAB, these laws of nature have to be short-circuited or impaired. Nothing against them but NABs are simply not natural. Thus, none of the ‘seven cardinal rules of brewing’ – if you will – as depicted in the diagram, can really be upheld. Therefore, consumers of non-alcoholic beers must be protected from pathogens in some other way. But how? Brewers of NABs must first perceive their product as something distinct from beer, i.e., non-beer, in order to better understand it. NABs could perhaps better be described as grain-based soft drinks. With almost all of the protections in beer compromised, brewers should be more vigilant and significantly heighten their microbiological quality control. Pasteurizing NABs after packaging is a must. There seems to be no way around it.

Or is there? New and innovative developments in this field are emerging. Recently, at the Craft Brewers Conference in Indianapolis and the EBC Symposium in Budapest, the authors were able to experience firsthand and listen to data presented on fascinating and novel approaches to these issues. Reverse osmosis coupled with a continuous fermentation process, referred to as ‘nested fermentation,’ is a method which has been developed to greatly concentrate the beer prior to shipping. This concentrated product is reconstituted at the destination through blending with water, pure alcohol and CO2 before being served or packaged. If the beer is meant to be non-alcoholic, then only water and CO2 are added back. If sufficiently concentrated, the lack of water activity keeps any microbes contained within it in stasis, as is the case with honey. One of the purposes of this process is to reduce the substantial greenhouse gas emissions resulting from refrigeration, packaging and shipping. Furthermore, concentrated and reconstituted beer also reduces some of the aforementioned risks to consumers, though it may not completely negate them. If not, it is not difficult to pasteurize the concentrate, as the volume has decreased considerably and it contains next to no dissolved CO2.

There are many more advances in the pipeline, and any number of combinations of these innovations or ones as yet in development will no doubt provide us with novel ways to produce cereal grain- and hop-based non-alcoholic beverages that are not only a very healthful alternative to sugary soft drinks but also very satisfying to people like the authors, longtime consumers of regular old traditional beer.

Keywords

quality control brewing technology microbial growth non-alcoholic beers

Authors

Nancy McGreger, Christopher McGreger

Source

BRAUWELT International 2025