Why big companies like AB-InBev are not prompt payers

For the cognoscenti, it’s just a metric by the name “negative cash conversion cycle” but it basically measures the time gap for a company between taking in cash from customers and paying its suppliers. Delaying payments to suppliers has apparently become fashionable. As Stephanie Strom reported in the New York Times in April this year: “In the past, extended payment terms often were a signal that a company was experiencing worrisome cash flow problems, but these days big, robust companies are imposing new schedules on suppliers as a business strategy.”

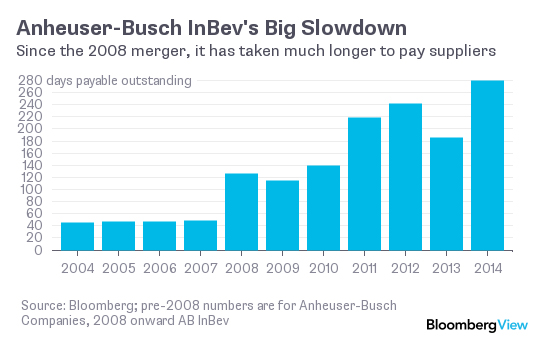

An article by Bloomberg (30 September 2015) argues that it was the Brazilians behind brewer AB-InBev who made the tactic popular. The old Anheuser-Busch was not immune to it either. In 2007, says Bloomberg, Anheuser-Busch got paid eight days before it paid its suppliers, on average. But in 2014, the gap for AB-InBev was 176 days.

“For a private equity firm such as 3G [the private equity vehicle set up by the Brazilian shareholders of AB-InBev], cash is king, so getting it sooner and paying it out later is something to strive for”, says Bloomberg.

But, as Bloomberg concludes, “taking it to the lengths that AB-InBev has is pretty obnoxious. The suppliers who have to deal with these extended payment terms tend to be smaller and have fewer resources than the companies delaying payment. Even with the extended terms, 47 percent of the suppliers surveyed earlier this year by Taulia, a company that facilitates supplier payments, reported that their customers paid later than promised. Maybe this is one explanation for why big companies have been on the rise and business dynamism on the decline.”