Becker, Woods and Rooney and the duplicity of celebrity endorsement

It’s amazing how much a brief fling can cost … even if it only lasts five seconds.

That’s reportedly how long tennis star Boris Becker said he spent having sex with Russian model Angela Ermakova in a linen cupboard in London’s posh Nobu restaurant on 30 June 1999.

But it was apparently long enough for Ms Ermakova to become pregnant and later give birth to a daughter, Anna. It was also enough for a London court to grant a “generous” financial offer from Becker to support the child. British media reported Becker gave Ms Ermakova GBP 2 million (EUR 2.3 million).

The serial adulterer Tiger Woods was not let off so cheaply by his wife. The golfer will have to pay a staggering USD 750 million (EUR 550 million) divorce settlement to his wife Elin, reports in the U.S. claimed in June 2010.

In that respect, Mr Rooney’s alleged cavorting with prostitutes came cheap. British tabloid newspapers could not conceal their delight at the news that he paid prostitute Jenny Thompson an “ugly tax” (his nickname is Shrek because of his looks) to the order of GBP 1,200 (EUR 1,400) per pop so that she would bed him seven times in four months. Hopefully, Mr Rooney will only face a lengthy period in the spare room and not be taken to the cleaners by his wife. Because that could cost him dearly.

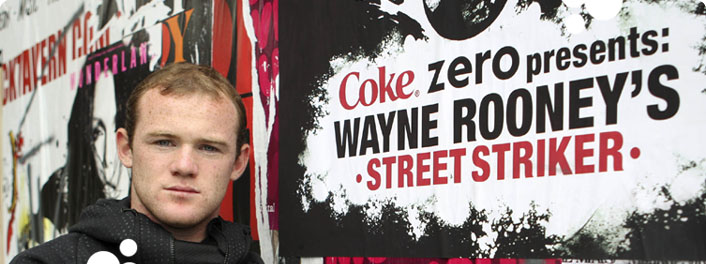

Mr Rooney is said to earn about USD 16 million a year: USD 8 million on the pitch and USD 8 million off it from endorsements including Nike, Tiger beer and Coca-Cola.

Celebrity endorsement has been a popular marketing tool – but it has never been without pitfalls. Because celebrities exist in the spotlight, surrounded by paparazzi eager to turn a stolen moment into a quick buck, the risk of getting caught doing something embarrassing is much higher than for the average Joe.

That’s certainly the case with athletes. Becker, Beckham, Woods, Rooney, the list is endless. And don’t get us started on Paris Hilton.

But why do corporate sponsors still throw up their arms in surprise and cancel their contracts when their celebrities do something naughty?

Isn’t there always the danger of them committing something unmentionable?

Perhaps this is taken for granted.

There’s a better way for companies to spend their marketing dollars. Celebrity spokespeople are expensive and risky, and they don’t always pay off. If consumer goods companies think their brand is in need of additional pull, instead of borrowing it from a celebrity, they should develop it themselves.

Sometimes consumers would not mind being taken for the adults that they are and not have some talking head plus their well-publicised antics and tawdry scandals thrown into their faces.

After all, celebrity endorsement has never made us pick a product.