Getting corporations to cough up on tax

Each time us lesser mortals receive our annual tax statements and can see for ourselves how many of our hard-earned dollars or euros end up in the taxman’s grubby hands, who does not feel like going over to the taxman’s office and turning Viking? You know: burn, ransack and pillage.

In Britain “doing a Viking” has become a popular form of protest for campaigners out to name & shame companies for tax dodging.

On 26 March 2011, during broader protests against government cuts, a group called UK Uncut made headlines when about 1,000 people rushed into the Fortnum & Mason store in London, famous for its picnic hampers, because its owners are at the centre of a GBP 40 million tax avoidance row.

In January UK Uncut had already staged about 30 protests against Boots and Tesco outlets calling on these retailers to pay their tax, which the campaigners say they avoid by using complex financial structures, some based off-shore.

The supermarket chain Tesco, which recently posted record profits of GBP 3.8 billion for the year to end February 2011, seems to have become the focus of protests. Campaigners accuse Britain’s biggest supermarket chain of dodging more than GBP 100 million in contributions. They have pledged to stage sit-ins and strip shelves of products over the summer.

First SABMiller, now Tesco and Boots: under the broad banner of “tax dodging”, these companies are being accused of various manoeuvres which in fact seem to be perfectly legal and often desirable (who wants to pay too much tax?) but morally reprehensible.

At the end of April 2011, the Economist newspaper, not exactly the paragon of left-wing radicalism, listed various companies for tax dodging.

“Vodafone is being criticised for paying the British government only GBP 1.2 billion (USD 1.9 billion) instead of the GBP 6 billion activists claimed it owed, to settle a tax dispute. Yet the government declared itself happy with the amount paid. The notion that GE paid no taxes in 2010, and even got a refund, seems to have come from a misreading of its accounts. Even so, the firm says it will have only a “small” American tax liability for last year, partly because of its “six sigma” approach to exploiting legal loopholes. Citigroup’s huge tax deductions are the result of its losses in the financial crisis. Fortnum & Mason was a target because its parent company has a big stake in a firm accused of using a holding company in Luxembourg to avoid GBP 40 million in British taxes. And so on.”

The tax-dodging claims have struck a chord with voters worried about rising taxes.

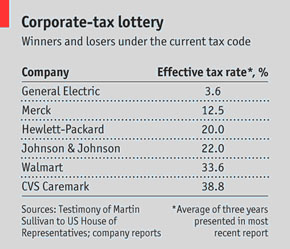

The Economist reported that in March this year a British parliamentary committee began an inquiry into corporate tax avoidance. A congressional panel in America heard evidence in January from Martin Sullivan, a tax expert, of the drastic variations in the effective tax rates paid by different American firms, even ones in similar industries.

A solution to this problem would be to introduce a radically different system in which firms are taxed not where they say they make profits but where they generate sales: i.e., where their consumers are.

This would make sense, argues The Economist, as it is relatively simple and would surely shift much of the tax base to bigger economies from tax havens.

However, concludes The Economist, it is a long way from what is being considered, at least in Britain and America.

On 1 May 2011, the Baptist Union of Great Britain voted to campaign against multinational companies that avoid paying tax in third world countries. It has also said it will support ChristianAid and its “Trace the Tax” campaign, which calls upon governments to enforce country-by-country reporting in order to make multinational companies more transparent about the profits they make and the taxes they pay in each of the countries they operate in.

As The Economist reminded its readers, politicians are keener on talking about reform than on reforming when it comes to corporate taxation.

Still, actions by ChristianAid and Actionaid help cut through the corporate obfuscation and make it clear that the failure of a large company to comply with a shared responsibility such as taxes is socially irresponsible.

Perhaps it’s time for corporations touting their corporate social responsibilities to voluntarily start cleaning up their acts.