Oasis right in the heart of action

Why would anybody want to build a new brewery in Kazakhstan? It’s not a terribly fair question because the question is loaded. It implies that Kazakhstan, a huge country south of Russia, is a somewhat peculiar market. Well, it is. Larger than Western Europe, it’s home to only 15 million people. Think Berlin – Paris and hardly anybody in between. Not good for shunting beer around. If you pardon the comparison, Kazakhstan is a bit like an island market in terms of brewers’ profits. Alright if you’ve got a monopoly. So-so if it’s a duopoly. And truly, shockingly bad if there are several players in the same field. Already, beer consumption stands somewhere between 30 and 40 litres per capita. Sorry, market researchers are a bit vague here. Whatever the exact figure, it would still be ok for an emerging market. It would be even better, nay spectacularly high, for a predominantly Muslim one, which is what Kazakhstan is.

But how much higher can beer consumption rise? In Turkey, another Muslim country, beer consumption is way below 20 litres per capita. And this is not for brewers’ lack of wanting or trying.

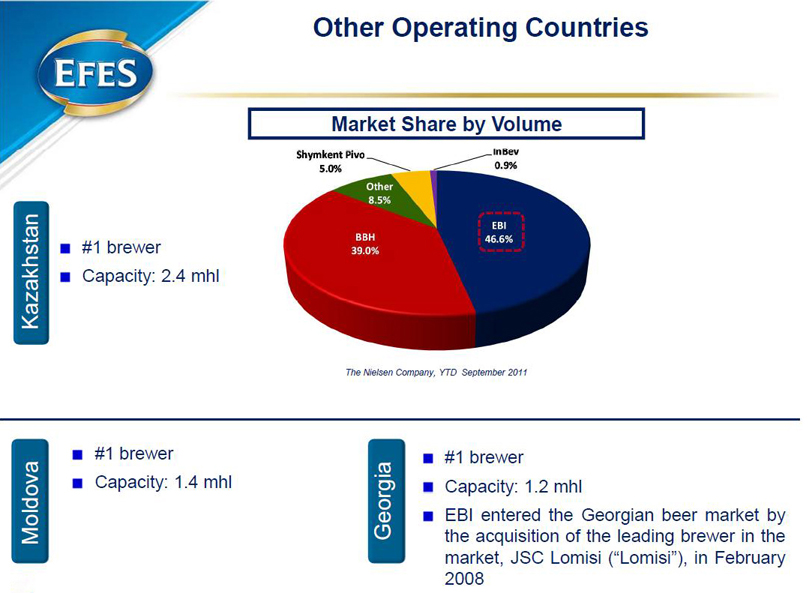

Which brings me back to my initial question: why would anybody want to build a new brewery in Kazakhstan? I think it becomes a slightly fairer question if you take into consideration that two long-established players have already cornered the beer market: Turkey’s Efes and Carlsberg. Together they allegedly control 86 percent of beer production which stood at 4.25 million hl in 2011, according to the recent Barth Report. Carlsberg has one brewery while Efes has three. Efes’ webpage curtly says: “For the present moment the company owns 2 breweries in Almaty region and [one in] Karaganda city.” Do they plan to have another one? Your guess is as good as mine.

Besides, running two breweries in Almaty, a city of 1.3 million people, must be one too many for Efes’ liking. But they cannot help it. One of these breweries dropped into their lap when Heineken decided to join forces there with Efes in 2008 and left the management of the Kazakh operations to Efes. Now why would Heineken have done such a thing, unless … well, unless they had struggled to continue going alone? Actually, Denmark’s Carlsberg followed Heineken’s example and in a flash of inspiration merged its Kazakh Derbes Brewing Company with Baltika-Almaty in 2010. In other words, the world’s major brewers knew when it was best to apply common sense: if you cannot beat them, join them.

My question, why anybody would want to build a new brewery in Kazakhstan, becomes fairer still if I reveal the location of the new brewery. It’s Almaty. From what I have heard it’s going to be a big brewery. The capacity is between 300,000 hl and 500,000 hl. That’s what I would call an optimistic capacity. Because to run such an operation profitably you will need volume. And quickly. You see, this is what is worrying me: Will Efes and Carlsberg welcome the new kid on the block? Will they say: “Come in, make yourself at home, let’s all be friends and share the spoils”? Will they generously relinquish some of their volume to accommodate the newcomer? If you remember what I said about island markets above, you will know the answer.

But the point at which my question becomes a really fair question is when you hear that the new brewery is going to be a newly built one. New equipment and all. Actually, the question that should be asked first and foremost is: Who would want to build a new state-of-the-art brewery in a city, a market, a region, which are by all accounts tough going? Rolling drums, please and pull back the curtain on Germany’s brewer Oettinger and Russia’s Oasis Group.

Oettinger is Germany’s major budget beer producer (10 million hl). As I have written before, for years, the secretive family-owned beer company, which does not disclose any financial details, has been the pariah of German beer because of its brand’s positioning in the discount segment. In the ranking of major German beer brands, the Oettinger brand was often ignored with the argument that Oettinger was not really a brand but merely a generic label stuck on its bottles. Then there was the not so funny discussion whether Oettinger was a brewery and not just a logistics company with five breweries attached. Oettinger self-distributes to the off-trade and ignores the on-trade.

Still, there is no denying that Oettinger Brewery has become a major player in the German market. It brews about 6.8 million hl of its own brand and another 3 million hl of own-label products. Moreover, it exports about 2.6 million hl (all figures for 2011), according to Dr Kai Kelch, a market researcher for BRAUWELT.

When contacted, Dirk Kollmar, Managing Director and owner of Oettinger Brewery was not available for comment. But he told other news services in July 2012 that the Almaty brewery will go on stream shortly. Those who have had a chance to visit Oettinger’s breweries in Germany will confirm that they are really well maintained. As they would be, given that he is a low-cost producer, whose beer costs less than EUR 7 per crate (10 litres) at the point of sale in Germany. Assuming that Mr Kollmar has a soft spot for high-tech brewery equipment, I would still like to query the wisdom of installing a brand new brewery in Almaty, especially as this runs counter to investment practice by the world’s leading brewers when it comes to markets which show similar characteristics to Kazakhstan.

You may call me a stickler but I think my question is a very fair one: why would anybody want to build a new brewery in Kazakhstan? The answer lies, as you may have guessed, with the investor, a company called Oasis.

Thrusting ambition

Oasis CIS is a holding company, registered in the, ahem, popular Russian tax haven of Cyprus (say media in the Ukraine), which owns beer and beverage companies in the former Soviet republics of Belarus, the Ukraine and Kazakhstan. In Kazakhstan, Oasis CIS already has a distribution business, currently operating under the name Oasis Kazakhstan, and a separate soft drink business. So when the new brewery opens these activities will be integrated, a spokesperson for Oasis, who decided to remain anonymous, told me in July 2012.

This does not answer my question why Oasis chose to build a new brewery in Kazakhstan. But if you will bear with me for a little longer, the answer will present itself.

The German brewer Oettinger and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) are minority shareholders in Oasis CIS. That much is public knowledge. The EBRD’s equity investment in Oasis CIS equals a 20 percent stake – again according to Ukrainian media. Last December, Mr Kollmar told the German Financial Times that he has “a 10 percent stake in Oasis”. The following day, he published a statement on his website that he does not own a stake in the Moscow Brewing Company (MBC). Those who saw the “correction” scratched their heads. Nowhere had Mr Kollmar mentioned MBC in the interview with the German FT. The reason he was – presumably – obliged to make this public statement is that there is a separate Oasis company that owns MBC, in which neither Oettinger nor EBRD have any stakes.

But the people behind Oasis and Oasis CIS are the same and they are not newcomers to the Russian beer industry. Oasis was established by the co-owners of private equity firm Detroit Investments, Eugene Kashper and Alexander Lifshits. That’s what Ukrainian news services say, who seem to be remarkably well informed. But only Mr Kashper has an executive post at Oasis where he is chairman of the board. In 1998 Mr Kashper and Mr Lifshits began putting together the Ivan Taranov group of breweries – PIT – in Russia with three plants. These they sold to Dutch brewer Heineken in 2005 for USD 560 million at an EBITDA multiple of 14. Not cheap. But those were the heady days in Russian brewing when everybody thought that beer consumption would rise … and rise … and rise.

What strikes me as highly interesting is that Oasis could set up MBC so soon after selling PIT to Heineken. MBC went on stream in 2008 with an initial capacity of 2.4 million hl. It was funded by Sberbank, Russia’s major state-controlled bank, and Detroit Investments, with a total investment of over USD 200 million, according to MBC’s website. Given how long it usually takes to plan and build a new brewery, Mr Kashper and Mr Lifshits must have already been plotting their comeback to brewing when they pocketed Heineken’s money. I would have thought that Heineken would have made them sign a long-term non-compete agreement. But what do I know.

Incidentally, MBC opened for business just when things in Russia began to turn bad. First the world economic crisis hit, then the government decided to rough up brewers by raising beer duty. Not an auspicious time for MBC to get going. By all accounts, MBC is a big brewery, although volume estimates vary widely. Sources close to Oettinger say it does 4.2 million hl, sources close to MBC say 3.5 million hl. Whatever the truth, MBC is probably the most modern brewery in Russia. It produces a wide range of beverages, including its own beer brands Zhiguli, Mospivo and Moskvas plus licensed beer brands such as Oettinger, Faxe, Breznak and Coors Light, amongst others.

MBC managed to gain traction in the Russian market because its own brands are mainly economy and lower mainstream brands. MBC’s portfolio of brands is huge, estimated to run to 60 brands. Its main brand, Zhiguli, seems to be a runaway success. MBC is also keen on new product launches. Hence, its brand portfolio is best likened to Gondwana: it shifts around. All the people I have spoken to agree that Oasis’s real strength lies in sales and distribution. That’s perhaps the reason why MBC has managed to increase sales in the much fought over Moscow market despite tough headwinds. What has piqued my curiosity is why the Oettinger brand is marketed as a lower mainstream brand. You can find bottles of Oettinger for 25 rubles in shops. For comparison: a bottle of an international premium beer can retail for anything between 50 and 150 rubles. This deliberate choice strikes me as odd. Admittedly, in its country of origin Oettinger is an economy brand. But that should not have stopped Mr Kollmar and MBC from going for a much higher positioning in Russia. If other German beer brands like Holsten and Löwenbräu, which are anything but premium in Germany, manage to claim a premium price in Russia, why can’t Oettinger?

I’d venture the guess that Oasis and Mr Kollmar initially chose volume over profits. Fine. Their decision. But this leads me to another question: if other brands have managed to nudge up their price positioning from mainstream to premium over the years, why hasn’t Oettinger? To press further: why is Oettinger’s volume in Russia still so low, despite having been in the market for four years? Again estimates vary widely. Sources close to Oettinger claim the brand is selling 600,000 hl per year, while sources close to MBC say it’s 150,000 hl. This being Russia, it’s hard to know the truth. Therefore, it may just be an evil rumour spread by his competitors that Mr Kollmar receives a licensing fee of EUR 2 per hl, which is very low by international standards. Usually royalties per hl range between EUR 5 and EUR 13 (or USD 8 – USD 15), I have been told. Still, Mr Kollmar may be satisfied with what he – allegedly – earns in royalties as this is about the same amount he is believed to net per hl in Germany.

In the right place at the right time

Oasis has been industrious in expanding its geographic reach. Oasis CIS, or Detroit Investments, or Detroit Belarus Juice Company (hell, it takes a lawyer or accountant to tell these different corporate takeover vehicles apart) first ventured into Belarus in 2008, where it acquired Staraya Krepost, the country’s leading juice producer. From what I could glean from media reports, the venture received funds from another prestigious international lender. In 2008 the World Bank’s unit IFC took an equity stake in the business and later supported the expansion of the Bobruisk juice plant, approximately 150 kilometers south east of capital Minsk. Oasis is also involved in brewing in Belarus, but I have no confirmed reports whether it owns a brewery there or uses another one to brew its beers, as at some stage I just gave up digging around Belarus, a country which is neither transparent nor a paragon of free media reporting.

More interesting is Oasis’ recent – 2011 – entry into the Ukrainian beer market. At 30 million hl beer production in 2011 and a per capita consumption of about 60 litres beer, the Ukraine ranked as Europe’s sixth largest beer market. With the exception of Ukrainian brewer Obolon (32 percent market share), the market is dominated by multinational brewers – Sun InBev (37 percent), Carlsberg Group (28 percent) and Efes (having taken over SABMiller’s operations with a market share of 6 percent). Funnily, the brewers’ self-attributed market shares don’t add up, as they represent 103 percent. Which would leave no room for Radomyshl and Persha Pryvatna Brovarnya (First Private Brewery), the latter of which is said to have a 2 percent share of the market. It was founded in 2004 and has since become the number five brewer in the Ukraine.

In 2011 Oasis bought the Radomyshl brewery, which had come to international renown thanks to its award-winning wheat beer Etalon. The deal also included the Ridna Marka portfolio of juice brands and, so I heard, a stake in First Private Brewery, which has a brewery in Lviv. Radomyshl is a fairly modern 350,000 hl (capacity!) plant located 100 km to the east of the capital Kiev. It had fallen on hard times and seen its beer sales crash. Although no transaction price was mentioned, analysts estimated it to have been below USD 40 million.

What will Oasis’ next steps be? It is widely assumed that Oasis CIS stands a good chance of buying the rest of First Private Brewery eventually. Already in April 2012 Oasis and First Private brewery consolidated their assets without giving further details. In a next step Oasis might try to go after brewer Obolon, whose finances in recent years are said to have been wobbly. Obolon might be willing to succumb to an offer from a “Russian” bidder like Oasis. But, then, again, the political power brokering behind Obolon is hard to fathom.

For Oasis CIS the task at hand is to revive Radomyshl. It will do that with the help of the Oettinger brand, which in the Ukraine is also positioned in the economy segment. It retails at 5.30 Ukrainian hryvnia (EUR 0.53) per bottle and slightly above Obolon beer at 4 hryvnia (EUR 0.40) per bottle, market observers say. Given Oasis’ sales and distribution strength its chances are good. Maybe they will find it a tad difficult to sway the Ukrainian consumers towards buying Oettinger. The Ukrainian beer market, on the whole, is not as attractive as the Russian, which dazzles with a multitude of brands. In the Ukraine, consumers are much more brand loyal than in Russia and content themselves with a fairly limited choice of brands, say six types of beer per brewer.

From the above, a picture has hopefully emerged. Considering the heavy amount of gossip floating around the industry (so thick you could actually scoop it up and sell it as fertilizer), Oasis is a force to be reckoned with in Russia and its adjoining markets. Its founders have shown a deft hand at planning their moves right from the start. As it seems to me, Oasis has brought Oettinger Brewery on board because it needed a volume booster brand in the economy segment, which is what Oettinger is. It would have also appreciated Mr Kollmar’s technical expertise. If anybody knows how to produce beer in the most cost-efficient fashion, it’s Mr Kollmar. That a Russian company can save on taxes if it has a German partner might have made Oasis even keener to get Oettinger on its side.

Judging from its founders’ previous history, I would not have thought that Oasis is in for the long-haul. Once it has turned its Ukrainian venture around and dug in its heels in both Russia and Kazakhstan, Oasis might seek an exit.

Who would want to buy Oasis, or Oasis CIS or both? I can immediately think of two brewers: Molson Coors and Heineken. Molson Coors earlier this year bought the central European brewer StarBev. They might want to move further east. Heineken would certainly eye MBC not least since adding it to its Russian business would give it a well-run brewery and some market share. Having been relegated to number four brewer in Russia as a consequence of the SABMiller-Efes tie-up, Heineken would not let such a chance slip it by.

To get back to my question as to why anybody would want to build a brewery in Kazakhstan: the answer is, in my humble opinion, capital transfer. Investing in Kazakhstan would be an elegant way of transferring profits out of Russia. Should the Kazakh venture prove successful eventually, fine. Should it struggle, also fine. Once the ultimate sale is done, the buyer could just pack up the brewery and move it elsewhere. You see, that’s what they mean when they talk about a win-win all the way to the bank.