How much worse can it get?

In 2012, German beer output is believed to have fallen 2 percent. That may not seem much given that sales spectacularly dropped 8 percent in April, 10 percent in September and 5 percent in December 2012 year-on-year. But if you bear in mind that beer consumption has declined for almost 20 years now at an annual rate of give or take 2 percent, then you will immediately understand how bad the situation really is.

So it’s kind of strange that almost all of Germany’s top ten beer brands showed some volume growth for 2012: Krombacher (1.4%); Bitburger (1.1%), Veltins (3.6%); Hasseröder (2.6%); Beck’s (0.2%); Warsteiner (0.5%); Paulaner (3.5%); Erdinger (0.3%) according to the trade publication INSIDE’s estimates.

The major exceptions were Radeberger (-2.2 percent) and Oettinger (-5percent). Ottinger, which happens to be Germany’s major cheap beer brand and is also Germany’s major brand in terms of volumes at 5.9 million hl in 2012. It will have given its competitors no small amount of schadenfreude that Oettinger too has been unable to break through the glass ceiling of 6 million hl domestically. By rule of thumb 6 million hl is the most any beer brand will ever sell in Germany.

However, on closer scrutiny, most of these volume growths were achieved at the price of heavy promotional activity or multiple brand extensions which have cannibalised core brands.

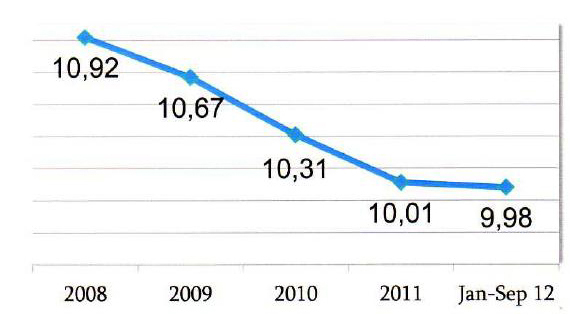

Already, the top ten beer brands sell over 70 percent of their annual volumes on promotion, up from 68 percent in 2011 and at a price of under EUR 10 per 10 litres, says GfK, a market research company.

If you want to fall into a bottomless depression, just visit any German retailer and walk down the beer aisles. In mid-January, I visited a Berlin supermarket and saw the following offers: Oettinger sold for EUR 4.99, Bitburger for EUR 8.90 and Hasseröder for EUR 6.48 (per 10-litre crate each). Hasseröder is a former premium beer brand that has been turned into a fighting brand by its owner AB-InBev in Germany.

That may help explain why Oettinger is struggling so hard. If a 2.7 million hl brand like Hasseröder or a 4.0 million hl brand like Bitburger are attacking Oettinger price-wise from above, why should price-conscious consumers chose Oettinger over an allegedly more prestigious brand which is on offer most of the time anyway?

The constant promotional activity by Germany’s major brewers has not only effectively erased the premium price segment, it has also made necessary price increases almost impossible. When Bitburger said in 2012 that it would not raise prices as of 1 October 2012 – contrary to earlier public announcements – because it feared huge losses in sales, the 30 or so family shareholders sacrificed substantial dividend payments. The price hike would have flushed an extra two-figure million euros in sales into their coffers during the fourth quarter 2012 alone, reckons Inside. Besides, what did this signal to Bitburger Brewery’s employees? More pressure on costs and jobs, obviously.

Ultimately, the erosion of Germany’s beer price architecture has made life even harder for regional brewers and their beer specialities. How can they expect consumers to fork out EUR 16.50 for 10 litres if the brand next to them on the shelf sells for half of that price?

The lesson is: If you want to see how big brewers manage to destroy market and company value like there was no tomorrow, look no further than Germany.