Is there a logic behind Germany’s alleged beer cartel?

After the flour cartel, the coffee cartel, the chocolate cartel, the potato cartel and now the beer cartel, it’s kind of hard to dispel the impression that the German food industry is a hotbed for illegal activities and that it’s only thanks to the Cartel Office’s prying eyes and severe crackdowns that unsuspecting consumers aren’t screwed by big and cunning corporations.

While investigations into the potato cartel and the beer cartel are still on-going, eleven manufacturers of confectionery were fined EUR 60 million (USD 80 million) this year for illegal price fixing. Also this year, 22 flour mills were penalised EUR 65 million over accords. Still, the highest fine for collusion to date was slapped on three coffee manufacturers in 2010: EUR 160 million (USD 211 million).

All these penalties pale next to the EUR 380 million that cement producers had to cough up, or the EUR 240 million that the manufacturers of liquid gas were forced to hand over for similar offences.

But as few Germans shoppers regularly buy cement, they can be forgiven for thinking that the only place where they are systematically and impudently charged more than they should be is at the supermarket till.

Strangely enough, this may not be quite true in the case of beer, where the German anti-trust watchdog is said to have found evidence that almost a dozen major German brewers and 24 brands colluded over prices “for decades”.

Actually, if you were to look at the development of the weighted overall average price for a crate of 10 litres of beer – on which rest the trustbusters’ watchful eyes – you can see that between 2003 and 2012 it declined by 5 percent.

2003 = 11.12 €

2004 = 11.25 €

2005 = 11.10 €

2006 = 11.15 €

2007 = 11.18 €

2008 = 11.65 € !!!

2009 = 11.49 €

2010 = 11.10 €

2011 = 10.70 €

2012 = 10.35 €

Following the price hike in 2008, the average retail price for beer rose 4.2 percent over the previous year, yet within a few years it dropped to a lower level than before the price increase.

Which makes many wonder: what kind of cartel is this that does not lead to higher prices for consumers?

This is not to deny that brewers may not have been engaged in shady accords. Often, cartels are set up by manufacturers of coffee, potatoes, chocolate bars – and perhaps beer – whose products offer less differentiation than cars or branded clothing. The more homogeneous a range of products, the more difficult it is for manufacturers to charge higher prices, hence they may opt for illegal agreements.

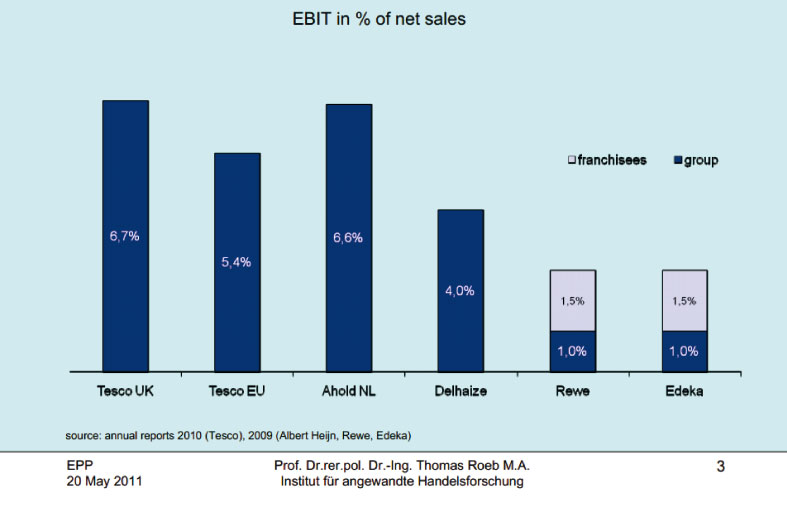

Secondly, cartels are often primarily directed against the powerful retailers and only indirectly against the millions of consumers. In Germany, the five leading food retail groups (Edeka, Rewe, Metro, Lidl and Aldi) control an estimated 75 percent of food sales. The discounters alone accounted for over 40 percent of total sales in the food and grocery market in 2012. Because retailers continually demand lower prices, manufacturers try to resist this pressure by colluding.

If, in view of actually falling retail prices, the German beer cartel looks like a botched affair it is because of cut-throat competition, fomented by the all-powerful retailers. Through concerted – but still illegal – price hikes, brewers may have tried to make up what they lost before. Unfortunately, through their promotional activity they then, bit by bit, relinquished their “successes” to the retailers.

However, there is one aspect to the beer cartel which does warrant bearing in mind. It’s called “killing off competitors”. Unless you are a conspiracy theorist, who does not require proof for such a bold assumption, the rest of us may never find out if this was intended by the cartel or came as a welcome side-effect.

Nevertheless, it’s a fact that in Germany’s declining beer market the major brewers have maintained or even grown market shares because they have been able to absorb rising costs while continuing to offer beer at incredibly cheap prices.

Many of the smaller brewers have not been so lucky. Between 1993 and 2012, over 110 breweries with an output between 100,000 hl and 1.0 million hl, had to shut down. At present there are still about 1,300 breweries operating in Germany. Given that consumption is forecast to go south by an average of 2 percent per year, anybody can work out on the back of an envelope how many more brewers will turn into roadkill.

As I see it, competition among brewers in Germany is mainly about capital: who’s got the most dosh and can survive over an extended period of shrinking returns.

Alas, this is an area the anti-trust watchdogs won’t sniff out. Nor will they investigate the effects all those proprietary returnable beer bottles, launched by the major brewers, have on their smaller rivals’ costs. In Germany, where returnable (and refillable) bottles are compulsory, all too often brewers receive crates with returnable bottles which are not theirs. The average rate of “stray” bottles is 30 percent per crate. A medium-sized brewery (200,000 hl) recently complained that sorting out these strays costs them about EUR 300,000 per year. The Association of Private Breweries in Germany, which represents 800 small and medium-sized breweries, has asked the major brewers to return to a generic returnable beer bottle for fear that its members will cave in under the cost burden, but no luck.

The anti-trust watchdogs may or may not find evidence of illegal agreements among brewers. As their investigation is mainly limited to what they consider “hard-core cartels” to the disadvantage of consumers, by which they mean agreements on prices, sales quotas and the distribution of markets, they will probably – by default – turn a blind eye on the cartel’s more insidious consequences: the stifling of smaller competitors by lowering retail prices of beer even further.

If, in years to come, more and more brewers bite the dust, the Cartel Office will merely consider them collateral damage. In the Cartel Office’s own logic, a broad oligopoly is the best precondition for optimal competition in an industry.

Which leads me to the most pressing question: how many players would the Cartel Office consider a "broad oligopoly" in the brewing industry? I’d say: two handfuls of strong – albeit easier-to-control – companies.

At the end of the day, we may never be able to detect a comprehensible logic in the German beer cartel. By the same token, however, this does not mean that there is no method in this madness.

The price of cheap – the biggest German food retailers are far less profitable than their European counterparts