German wheat beer: how to kill a winner

Wheat beers have long enjoyed the highest prices for beer in Germany. They are the measure of how much Germans are prepared to pay for beer at the most. Now that AB-InBev is heavily discounting its national wheat beer brand Franziskaner, German brewers fear the whole price architecture for beer will collapse.

Talking to German brewers you could easily get the impression that relations between them and AB-InBev are somewhat strained. That’s hardly surprising: here you have the proud owners of family businesses going back generations, if not centuries, who can wax lyrically about brewing traditions and the quality of their beers, and there you have even prouder envoys of some distant Brazilian bosses, whose sentences are littered with acronyms like KPIs and COGS.

Cultural schisms aside, relations took a turn for the worse this year when it became known that AB-InBev had turned whistleblower in Germany’s ridiculously ineffective beer cartel, thus escaping a fine while plenty of German brewers had to stomach the grand total of EUR 340 million (USD 440 million) in penalties.

It did not help that the German news magazine DER SPIEGEL in July published a long story about AB-InBev, whose caption “Die Biermaschine” (“the beer machine”) already said it all: that AB-InBev’s business was finance-driven and beer merely an underlying product.

The authors of the article had done their research. They showed how far the Brazilians were prepared to go in their notorious cost-cutting zealotry: rationing stationery, extending terms of payment for their suppliers, forcing sales reps to pay for their company cars getting a car wash, making everybody stay at budget hotels. Even more revealing: when the SPIEGEL journalists visited AB-InBev’s European boss Stuart MacFarlane in Leuven, he himself served them coffee in plastic cups from a vending machine.

The article created quite some buzz in Germany. To German brewers’ ears, AB-InBev’s talk of “ownership culture”, which expects employees to stretch themselves to reach targets (or else get the sack) sounds like travesty. As they point out, AB-InBev’s German unit has seen seven managing directors leave in the past eleven years. Were they all over-achievers, they wonder?

What is more, AB-InBev has consistently failed to reach a 10 percent market share in Germany.

Several brewers remark that Germany is a beer market that does not fit AB-InBev’s operational pattern. The market is in decline by an average of 2 percent per annum; it is highly fragmented and brewers remain obstinately opposed to consolidation; wholesalers are fiercely independent and consumers stubbornly price-conscious. In effect, Germany is probably one of the few markets world-wide where you have something that warrants the term “competition”. Given that the top 10 brewers only control slightly over 50 percent of the market, it becomes clear that no single brewer can call the shots and set the terms for doing business – as you would in, say Brazil, where AB-InBev alone commands a monopolistic market share of 68 percent.

That, as a consequence, margins and profits are comparatively low in Germany and very much under a downward pressure is the unfortunate corollary.

Never mind Germany’s declining beer sales and fierce price wars, the Brazilians refuse to change tack. As Carlos Brito allegedly told one German brewer: “We will not discard our principles just because of this internationally unimportant market.” Well, they once almost did. There is a rumour circulating that, after the USD 55 billion takeover of Anheuser-Busch in 2008, AB-InBev was prepared to exit Germany in order to get out of a liquidity glitch. Those in the know claim that AB-InBev was willing to part with its German assets for as little as EUR 1 billion (USD 1.3 billion) and hand them over to their German rival Radeberger – after having spent about EUR 3 billion on gobbling them up. Yet, when AB-InBev’s cost cutting fervour achieved the desired results, further sales talks were cancelled.

German brewers have wondered for long what AB-InBev hopes to get out of doing business in Germany as what it does appears to be diametrically opposed to what some German brewers do, namely raising margins through a consistent cost and profit management (it’s the latter that AB-InBev seems to ignore) . Several German brewers admit that profits are not yet what they would like them to be. Still, in the medium term they hope to raise their profits through bolstering their brands but without cutting corners on product quality and services.

What German brewers fail to see at AB-InBev is a genuine interest in its brands. Or why would it price down the Franziskaner wheat beer brand as it has been doing for at least two years?

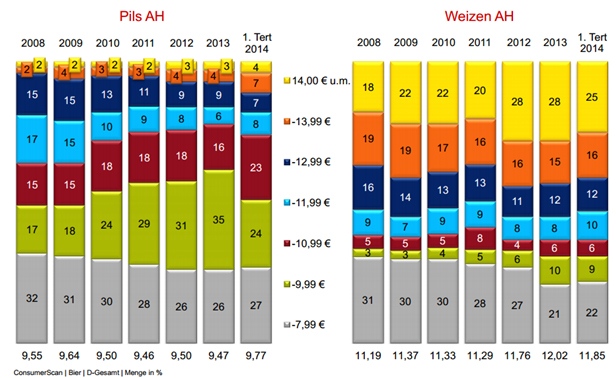

Wheat beers are the price leaders in the German beer market. Although the segment is small in terms of volume (only about 10 percent of the market), it commands retail prices far above most lager and pils brands. According to GfK, a consumer research outfit, in the first four months of 2014, 25 percent of all wheat beers retailed at over EUR 14 (USD 18) per crate (20 bottles x 0.5 litres), the German measure of all things beer, while only 4 percent of all pils beers could aim that high.

The national wheat beer market is basically dominated by five brands: Erdinger (1.7 million hl in 2013), Paulaner (1.5 million hl), Franziskaner (1.2 million hl), Krombacher wheat (241,000 hl) and Schöfferhofer (510,000 hl). All estimates by INSIDE, a German trade publication.

Looking at Drotax data for May and June, when the Football World Cup got under way, Erdinger and Franziskaner engaged in almost 230 major price promotions. This was to be expected. But while the majority of Erdinger’s, Paulaner’s and Schöfferhofer’s promotions were priced between EUR 13.50 and EUR 14.00 per crate, Franziskaner’s were priced between EUR 12.50 and 13.00.

The average price gap between Erdinger and Franziskaner was even wider in Bavaria, which is home to both brands and where wheat beers represent about 30 percent of beer consumption.

During the first half of 2014, in the region around Munich, Franziskaner generally retailed at EUR 1.40 per crate below Erdinger, which sold at EUR 14.30 to 16.00. Worse still, in neighbouring Swabia, Franziskaner retailed at EUR 2.10 per crate below Erdinger.

If you look at volumes sold during promotions, in and around Munich it’s been estimated that Franziskaner flogged off 30 percent of its beer on promotion, whereas Erdinger only did 16 percent.

To German brewers this only indicates one thing: that Franziskaner depends on promotions for a sizeable bulk of its sales and not on loyal customers or stable prices.

Rival brewers and wholesalers are growing increasingly concerned that Franziskaner’s pricing policy is going to negatively impact the whole wheat beer segment and push down prices and profits for all.

But unlike the privately-owned German brewers who can set their own goals, what can AB-InBev’s people do in Germany but milk their brands and business for all they are worth in order to reach their externally imposed targets? Following a general beer price hike in early 2013, AB-InBev already saw volumes of its two major German brands decline massively in 2013: Beck’s lost 190,000 hl (or 7.2 percent) and Hasseröder 345,000 hl (12.5 percent). Only Franziskaner managed a sales increase of 80,000 hl or 7.5 percent (but thanks to lower prices). In the end, it was to no avail: the whole German unit lost 7 percent over 2012 according to INSIDE’s estimates. AB-InBev eventually admitted to a 7.1 percent volume decline in Germany in 2013.

In the grand scheme of AB-InBev’s things, Germany accounts for 2 percent of its volumes. In Brazil alone it ships this much beer in a month. This shows why Germany really is an “internationally unimportant market” to AB-InBev.