Government mulls introduction of sugar tax

Governments have every reason to be concerned about the damaging impact of sugar on health – from people’s rotting teeth to type 2 diabetes and bulging waistlines. But the jury is still out on the question if a sugar tax is the appropriate measure to make people change their consumption habits.

This has not stopped the Belgian government from pushing ahead with a “sin tax” on “unhealthy” foods and beverages, as was reported at the end of July 2015.

What the Belgians mean by this tax is not immediately clear. It can only involve some sort of sugar and fat tax. Insiders are rightly worried that all beverages containing sugar or sweeteners, namely soft drinks, Radlers, fruit beers and beer mixes like Desperados (Heineken), will become a target.

Although the Belgian government is only deliberating on a sugar tax at the moment, it is clearly occupying a vanguard position in Europe. The anti-sugar front may be most vocal in the UK, where the government has repeatedly ruled out a sugar tax, but it has already scored a victory in France. The French government introduced a sugar tax in 2012, albeit on beverages without alcohol, namely sodas.

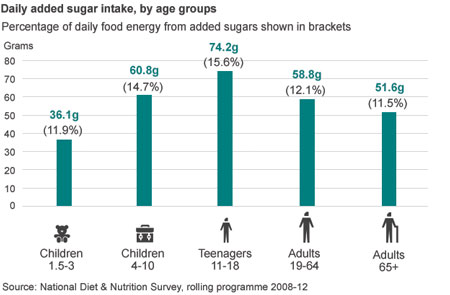

The opposition against sugar is mounting. In July 2015, Britain’s doctors called for the UK government to impose a 20 percent tax on sugar-sweetened drinks to pay for subsidies on fruit and vegetables in an effort to slow the obesity epidemic. A report from the British Medical Association demands tough regulatory action on a whole range of issues, from taxation to a clampdown on the marketing of unhealthy food and drinks to children, mandatory standards on the food available in all schools and bans on clusters of fast food outlets, media said.

The doctors’ call is backed by U.S. research. A study by the American Cancer Society found that taxation on sugary fizzy drinks does help fight obesity. But it concluded that, rather than imposing a flat tax on the volume of drinks consumed, the sugar levels in drinks should be taxed to encourage manufacturers to lower the levels of sugar in their products.

In 2011, Britain’s Prime Minister David Cameron said his government was considering taxes on unhealthy foods, which would include those high in sugars, salt and saturated fats. However, when the Life Sciences minister George Freeman raised the issue recently, he was slapped down. Asked in May 2015 if a sugar tax was being considered, the Prime Minister’s spokesman reportedly said a definitive no. The government would be looking at other ways of tackling obesity, the spokesman added.

Contrary to Mr Cameron’s early statement, the UK government has since chosen to address obesity through a voluntary responsibility deal with the food industry, which asks companies to make pledges on measures such as labelling and cutting calories in their packaged food products.

The Belgian government, to all appearances, now wants to best the UK government by pushing ahead with a sugar tax, probably buoyed by the Mexican experiment.

In January 2014, Mexico implemented a tax on sugar-sweetened drinks, adding around USD 0.07 per litre, which equated to around 10 percent of the price. The measure applied to all drinks sweetened with sugar, not just carbonated drinks.

Some studies argue that the tax in Mexico led to an average 6 percent decline in demand in 2014. The greatest change allegedly occurred in the most vulnerable low-income households, where consumers were able to cut consumption by 17 percent and shift their dietary habits toward diet soda and natural juices that do not have extra sugar added.

However, these findings were immediately discredited by other experts as incomplete and by interested parties. Moreover, even if there was a decline in consumption, the effects would have been minimal. U.S. consumption of soft drinks has dropped 14 percent between 2004 and 2014 – but without any visible effect on the nation’s girth or health.

Same in France. Although the French government went further than Mexico’s and levied a tax on both sugar and sweeteners (to reach EUR 7.45 per hl in 2014 as it is indexed) because there is mounting evidence that drinking diet soft drinks may be as bad as – or even worse than – sugary drinks, estimates say that soft drink consumption in France merely decreased by 3.0 to 3.5 litres/person per year. This represents between 12 percent and 15 percent of the initial consumption. The drop appears significant unless you know that soft drinks’ share of throat is only 11 percent in France. No wonder a 2014 study (“Food taxes and their impact on competitiveness in the agri-food sector”) argues that the decrease was low and does not support the argument that it has led to any change in consumption behaviour.

Do sugar taxes help fight obesity? The answer is a resounding “maybe”. The truth is that “sin taxes” work only at high levels and on the proviso that (a) consumers cannot get around them by switching from brand leaders to budget brands and (b) producers/retailers effectively pass them on to consumers.

For example, some retailers in Berkeley, California, which in 2014 implemented a soft drink tax, did not initially pass the tax on to customers, but paid it out of their own pockets because they feared losing business to stores in nearby cities if they charged customers the full price.

There’s no doubt, though, that sugar taxes are a fast and reliable way for governments to collect money. See France. While the initial objective of the sugar tax in terms of revenue generation was EUR 280 million, EUR 375 million were effectively collected in 2013.

Historically, governments the world over have been very creative in spotting opportunities to generate revenues. Over time, there were taxes on windows, candles, playing cards, dice, soap, starch, gloves. The list is almost endless. There were even taxes on hats (an early form of “tax the rich” in the UK) and beards (in Russia under Peter the Great who wanted his countrymen to adopt the clean-shaven look that was common among men in western Europe).

Unlike Belgium’s soft drinks producers, the country’s brewers could be forgiven for secretly laughing the sugar tax off as yet another governmental money-spinner, underlining governments’ duplicitous habit of taking with one hand what they give with the other. Europe, like the U.S., is notorious for its agricultural subsidies and regulatory interferences, which also benefit sugar production (corn in the U.S., beet root in Europe).

Besides, Belgium’s brewers don’t sell huge amounts of Radlers and beer mixes which would be affected by the tax – whenever it is implemented.

Nevertheless, brewers have every reason to feel concerned. No matter how you look at it, a sin tax is a sin tax. A sugar tax may not harm brewers’ sales in actual fact. Yet, in the long run it will change the general perception of beer: from a “natural beverage” towards an “alcoholic” soft drink.

Should this sink in with the authorities, brewers will be in a bad way … but our peoples no slimmer or healthier, it is to be feared.

Sweet (or rotten toothed) Britain

Keywords

Belgium international beverage market taxation

Authors

Ina Verstl

Source

BRAUWELT International 2015