AB-InBev

A rout in AB-InBev's share price since the beginning of this year has led plenty of commentators to ask if the business model of world's major brewer, which was based on a sequence of takeovers ("buy and build"), has not run its course. When the Brazilians pulled off InBev's acquisition of Anheuser-Busch in 2008, which ultimately became AB-InBev, it seemed like a guaranteed winner. AB-InBev had such success generating value in the global market, it appeared that Big Beer was a logical target, given its enduring power in the market.

As was pointed out in a recent post on Motley Fool, "AB-InBev has consolidated about as much market share as it can globally, adding to its portfolio assets like SABMiller and a number of craft breweries. But the beer giant has lost market share and profitability in the last few years, undercutting the idea that bigger is better in beer."

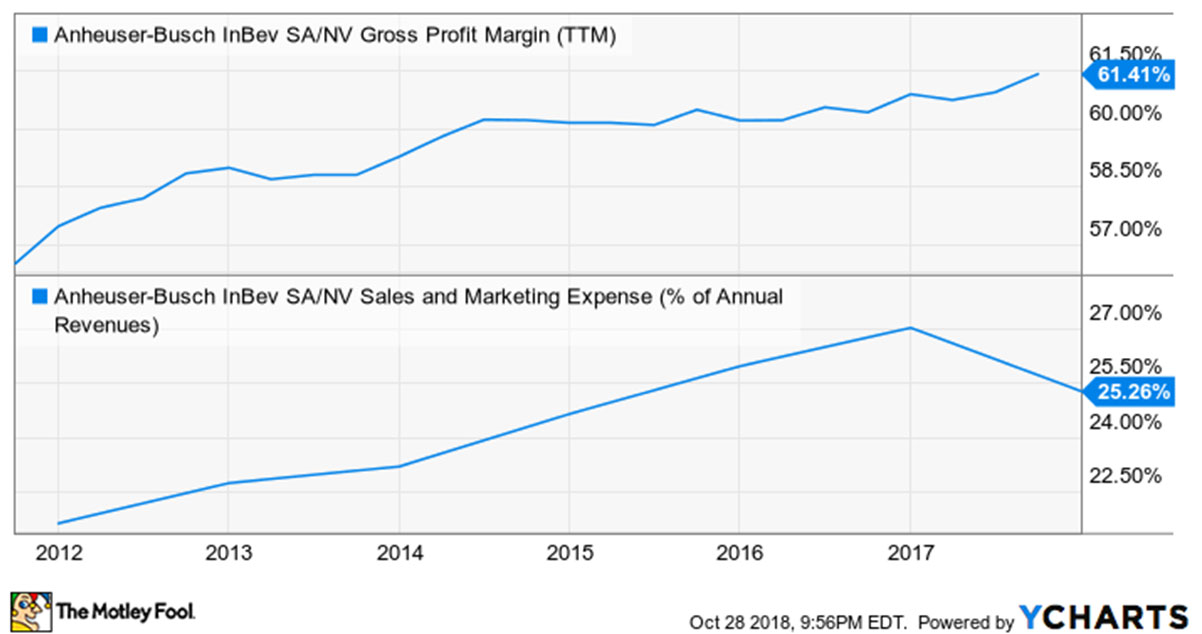

The idea behind consolidation in the brewing industry was simple. Because of their size and market clout, waning competition between brands would allow the Big Brewers to slowly raise prices and expand margins. The chart shows that AB-InBev has implemented this strategy. Its gross margin has stepped up steadily higher over the past decade.

However, what AB-InBev did not - or could not - anticipate was that macro beer brands on the whole are falling out of favour with consumers and losing market share. AB-InBev's volume sales have stagnated in recent years and it needs to spend more money on sales and marketing than it did ten years ago, just to maintain its volume.

In the US, the world's most profitable beer market, craft brewers have increased their market share from 5.7 percent in 2011 to nearly 13 percent 2017. Internationally, craft beer does not enjoy this kind of market share, but the trend towards local beers is happening all over the world, and that is bad news for AB-InBev.

It probably also did not foresee that global beer volumes would stagnate. Since 2012, global beer output has hovered around the 1.96 billion hl mark. This has impacted AB-InBev's ability to capture any easy growth. Moreover, the hype over the BRIC countries has had a hard landing. Beer consumption in China and Russia has dropped massively, while in Brazil the decline has been less significant but noticeable nevertheless. Most recently, emerging-market currencies have taken a plunge, which would have been another unexpected blow.

AB-InBev has done its best to cut costs and hike margins. But low or no growth and rising expenses have undercut the entire conceit of making Big Beer bigger.

Mind you, AB-InBev continues to be a highly profitable business, which is controlled by wealthy investors, who can shrug off share-price gyrations. They can use the business as a cash cow, but there is no indication that AB-InBev will be a growth stock in the future. Without takeovers, which would allow AB-InBev to continue doing what it did best in the past, namely buy and build, AB-InBev is facing years of humdrum slog.

Hence the share price decline. At the end of October 2018, the price dropped to a 12-month low of USD 74. This means AB-InBev's share is 30 percent down on the year's high, touched in January, and is way off the record high of USD 122, reached in 2015 shortly after the USD 107 billion bid for SABMiller was announced.

The issue to watch is this one: How quickly will AB-InBev pay back its current debt? After it had bought Anheuser-Busch in 2008, it took AB-InBev only until 2011 to reduce its debt to a more manageable (read safer) 2.5 times EBITDA. Taking over SABMiller meant that AB-InBev's debt rose to 6.5 times EBITDA. It was still 4.87 times EBITDA in July 2018. At the time AB-InBev said that it was committed to bring down debt to the level of 2 times EBITDA, without saying when it plans to reach it.

No doubt, without any deals on the horizon, AB-InBev is now a mature business. It will need to prove that it can act like one.