Pubs a goldmine for big brewers and a coalmine for craft brewers

Craft beer sales may be on the rise in Australia, but craft beer brewers are still struggling to make serious inroads into the lucrative on-premise sector. Why? Because they suspect that the country’s two big brewers have managed to protect their dominance over the beer taps of Australia’s pubs and bars.

Now the Australian competition watchdog (ACCC) has decided to sniff the sector out, conducting a confidential investigation into the draught beer market, initially targeting the major beer consuming state – New South Wales – with visits to numerous brewers and publicans in the past few weeks.

Whether anything “revolutionary” will come of this investigation into sales exclusivity contracts (as they are usually called) remains to be seen.

Perhaps this publication is a tad more pessimistic than others as a recent complaint against this practice in Mexico led to very few regulatory changes – something the ACCC must be aware of.

In Mexico it was a protest by SABMiller and some microbrewers that got the antitrust authorities going. Like Australia, Mexico is a beer market duopoly: in this case by AB-InBev and Heineken.

Last year, the Mexican antitrust authority ruled that brewers must limit exclusivity agreements in the on-premise sector to 25 percent of their total points of sale, gradually reducing that to 20 percent by 2018. Analysts deemed this “not that harsh” for the big brewers because existing contracts that typically last three to five years were allowed to run their course.

What is more, restaurants and bars only account for around 15 percent of beer sales in Mexico, it was reported. The bulk of beer sales – about 50 percent – is channelled through corner stores, many of which agree to sell only one of the two brands in exchange for beer-logo awnings, signs or refrigerators, as well as discounts, credit or assistance with local permits, the Wall Street Journal wrote at the time. Incidentally, the anti-trust authority decided to turn a blind eye on this.

The situation in Australia appears to be somewhat similar to Mexico, although Australia’s on-premise sector would be much more valuable than Mexico’s, at least relatively speaking.

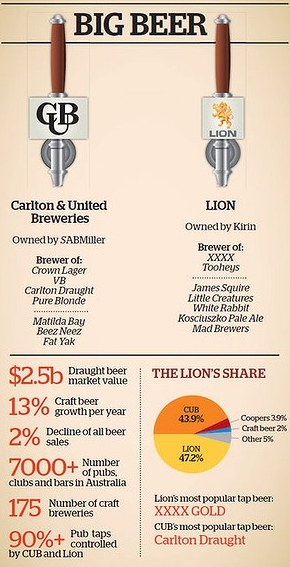

On 1 June 2014, The Sydney Morning Herald newspaper ran a long and interesting piece on the country’s pub industry. It said that “every year, Australians consume AUD 2.5 billion (EUR 1.7 billion) worth of draught beer. As much as 95 percent of it will be produced by the two multinational beer companies that control Australia’s best-known beer brands: Lion, owned by Japanese company Kirin, which sells Tooheys, XXXX and James Boag’s; and CUB, owned by SABMiller, which holds the VB and Carlton labels. Other significant players, such as the family-owned Coopers brewery, Japanese giant Asahi Breweries and Coca-Cola Amatil, which recently re-entered the draught and bottled beer market, are also in the mix. This adds to the cutthroat competition for market share in the tap beer market, which is much more profitable than bottled beer and attracts 40 percent less excise tax.”

Although Australia’s craft beer movement took off in the 1980s, craft breweries still only command a tiny 2 percent share of Australia’s total beer market. “But craft beer is bucking a long-running downward trend in overall per head beer consumption in Australia, which has declined from 141.7 litres a year at the start of the 1990s, to 93.1 litres last year,” the newspaper wrote.

Industry sources estimate that craft beer consumption is growing at 13 percent annually with the number of craft breweries having jumped from about 86 a decade ago to about 175.

As visitors to Australia will know, the diversity of craft beers found all over Australia stands in sharp contrast to the selection on tap at pubs.

The newspaper quoted Thunder Road Brewing Company’s founder Philip Withers, describing the situation thus: “a goldmine for them [Lion and CUB] and a coalmine for the rest of us.”

Obviously, the country’s two major brewers – Lion and CUB – don’t want to let go of the draught beer market as they themselves face two powerful retail groups, which control an estimated 60 percent of the packaged beer and drinks market. Their determination to drive down suppliers’ margins is well known.

To matters worse, the two retailers – Coles and Woolworth’s – are also heavily involved in the pub sector.

The major brewers’ weapons of choice, says the newspaper, are pourage contracts, signed between beer companies and publicans, which lock up taps for the exclusive use of one beer company for two or three years.

In return, the publicans get various benefits, such as refunds on the price they pay for beer, business development allowances, upgraded tap systems and fridges paid for by the beer companies.

Publicans freely admit that these benefits can be the difference between staying in business and shutting down. To all appearances, Australian pubs (or hotels as they are called locally) in good locations make heaps of money. Otherwise they would not look the way they do. But while a few do well, many others seem to be struggling. That’s perhaps the reason why they readily accept the big brewers’ strict contracts.

It needs to be pointed out that in many or even most markets around the world “exclusivity contracts” are not uncommon. Think of the retail and hospitality industries. They are certainly not illegal. Most coffee shops do deals to sell a specific brand of coffee in return for cups, machines and rebates. Beauty parlours are often tied to certain brands and soft drink operators do exclusive deals with certain outlets.

But the key issue in Australia is whether these exclusive dealings “substantially lessen competition”. This is what the competition watchdog will have to weigh up as it conducts its investigation.

According to the newspaper, a number of Australia’s 175 craft breweries and publicans have supplied information to the regulator – including contracts, emails and first-hand experiences.

One brewer willing to go public on this is Adelaide’s Coopers brewery, Australia’s third biggest beer producer and still family-owned. Coopers holds about 4 percent of the domestic market, which is significantly below the share controlled by the two the big brewers, but substantially bigger than any craft operation.

Despite Coopers’ financial resources and a history stretching back over 150 years, it too has struggled to maintain its share of pub taps. Coopers too has to pay for taps to be installed in pubs and offer rebates to publicans. Coopers Chairman Glenn Cooper was quoted as saying that the market has become “more difficult and more expensive” in recent years.

Asked why he thought publicans signed up to the contracts, Mr Cooper had a simple answer: “Money talks”. Observers say that business is tough for pubs that don’t sign the contracts. “No contract means no discount, which makes it harder to compete on price with other nearby pubs. They are treated as ’spot’ customers and put at the bottom of the list for deliveries. Most concerning is they are not guaranteed supply at peak times”, the newspaper says.

As it seems, exclusivity contracts and their impact on competition, innovation and choice is a tough and complicated debate.

We shall see what conclusions the competition watchdog will draw from its investigation.